Ending Pandemic Unemployment Benefits Linked to Job Growth

Beginning in May 2021, 26 U.S. governors announced that their states would end some or all participation in pandemic-related emergency unemployment benefits (EUB) ahead of the federal programs’ September expiration. At the time, some of these governors echoed the concerns of business owners in their states that generous EUB were contributing to difficulties filling job vacancies, which were nearing all-time highs. Twenty-four of the 26 states halted their participation between June 12 and July 3.

The EUB programs were historic, extending the number of weeks individuals could receive benefits, adding $600 per week (later reduced to $300 per week) to recipients’ baseline benefits, and expanding program eligibility to contract and gig workers, who would otherwise not be covered. Many recipients of these enhanced benefits saw a more than one-for-one replacement rate on lost earnings. By contrast, typical pre-pandemic unemployment insurance benefits may have replaced 40% to 50% of lost earnings.

Data Show Early End to EUB Had a Positive Impact on Employment

In a recently released Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis working paper, we use this asynchronous halting of EUB to investigate the impact on jobs from ending emergency unemployment benefits. We compare the decline in EUB recipients and increase in employment across states in the month benefits were halted relative to surrounding months.

We found that terminating EUB had a statistically significant and quantitatively large positive impact on employment. In the three months following a state’s EUB termination, employment increased by about 37 people for every 100-person reduction in EUB recipients. This finding is robust when controlling for observable differences across states, including the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths and the share of employment in leisure and hospitality.The statistical procedure used to measure this jobs effect is called instrumental variables. The technique of “controlling for observable differences across states” is grounded in multivariate regression analysis.

Visualizing the Data

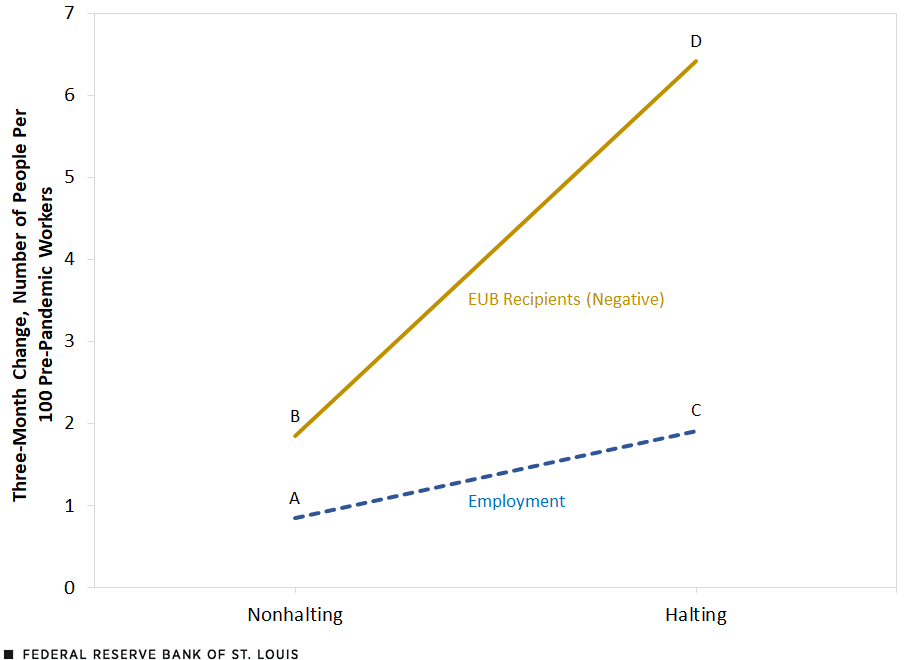

To make our analysis easier to visualize, we’ll now lay out a simplified version of the model used in our working paper. To construct the figure (see below), we first divided each calendar month from December 2020 to December 2021 into one of two groups by state: the 11 months in which the state did not halt EUB and the single month in which it did. For this first group, we computed the average change in employment (over a three-month horizon) for every state during the corresponding 11 months.We calculate this average using pre-pandemic employment to weight each state, in order to reflect the size differential across states. We have only 46 states (and Washington, D.C.) due to limited data availability. This average equaled 0.9, indicating that employment was increasing by about 0.9 individuals per 100 pre-pandemic employed people in nonhalting periods. This is labeled Point A on the figure.

Next, we computed the same average across states using their nonhalting months for the (negative) change in recipients. This number, labeled Point B on the chart, equaled 1.9, indicating that on average 1.9 individuals per 100 pre-pandemic workers were leaving the recipient rolls during the nonhalting periods.

Then, we repeated these averaging calculations for the halting months. Since each state halted benefits only once, these averages were taken simply using available data for 46 states (plus Washington, D.C.). These points are labeled Point C and Point D on the figure. On average, employment increased by 1.9 people and the number of recipients decreased by 6.4 people per 100 pre-pandemic workers following the halting month.

Three-Month Change in EUB Recipients and Employment per 100 Pre-Pandemic Workers

SOURCES: Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: Results are aggregated from state-level data using pre-pandemic employment levels as weights.

Halting EUB Stimulated Employment

The act of halting by a state was—on average—associated with a substantial rise in employment and a substantial decline in the number of unemployment insurance recipients relative to the other months. These observations led us to the conclusion that halting benefits stimulated employment.In formal terms, the conclusion that halting benefits caused employment to increase requires that the state’s decision to halt benefits was unrelated to unobserved random drivers. We discuss the support for this requirement (i.e., assumption), as well as the issue more generally in our working paper. We quantify this effect using the following calculations:

- The difference in the beneficiary reduction comparing the halting months with the nonhalting months: 6.4−1.9 = 4.5 people.

- The corresponding difference for the employment increase was 1.9−0.9 = 1 person.

- Thus, the employment change per reduction in 100 beneficiaries is the ratio of these differences: 1/4.5 * 100 = 22 people.

- In other words, for every 100 people who lost benefits, employment rose by about 22 workers.

This calculation derived from our simplified model is limited along two dimensions. First, it does not permit one to consider observable cross-state and cross-month differences in the data. Second, it does not account for the statistical precision of the estimate—i.e., whether the results could have occurred by chance.

Our working paper provides a more detailed and formal statistical analysis. We found that adding conditioning variables boosts the employment increase to 37 people for every 100-person reduction in EUB recipients; moreover, the statistical analysis establishes that the 37-person estimate is statistically different from zero.

The 2021 episode described in this post—featuring the asynchronous, and in some states, sudden—termination of EUB provided an excellent laboratory to explore the jobs effect of ending unemployment benefits. The strong positive jobs effect that the data uncovered offers another basis for public policy discussions. For example, states that ended EUB in the fall might have accelerated their employment recoveries had they opted for early program cessation.

Notes

- The statistical procedure used to measure this jobs effect is called instrumental variables. The technique of “controlling for observable differences across states” is grounded in multivariate regression analysis.

- We calculate this average using pre-pandemic employment to weight each state, in order to reflect the size differential across states. We have only 46 states (and Washington, D.C.) due to limited data availability.

- In formal terms, the conclusion that halting benefits caused employment to increase requires that the state’s decision to halt benefits was unrelated to unobserved random drivers. We discuss the support for this requirement (i.e., assumption), as well as the issue more generally in our working paper.

Citation

Iris Arbogast and Bill Dupor, ldquoEnding Pandemic Unemployment Benefits Linked to Job Growth,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 8, 2022.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions