The End of Emergency Pandemic Unemployment Benefits in 2021

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. government launched a number of programs that greatly enhanced unemployment benefits. While successful in mitigating the impact of lost income for millions of workers, the generosity and duration of the benefits raised questions about whether these programs created disincentives to seek employment. In this blog post, we will examine whether the loss of enhanced federal benefits affected participation in regular state unemployment insurance programs.

Erratic Endings to Programs

The question was further complicated by the fact that many states chose to withdraw from federal benefits early. In June and July of 2021, 26 states stopped providing Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), which added an extra $300 weekly to regular state program unemployment benefits. The FPUC program was one component of the federal response to the pandemic.At first, the add-on provided $600 per week of additional benefits; this was passed as part of the CARES Act passed in March 2020. The program was renewed in December 2020 and modified such that the weekly add-on was reduced to $300 per week. The remaining states continued providing FPUC through early September, upon which time the program’s federal funding lapsed.

Twenty-two of these 26 states also stopped providing two additional federal unemployment benefit programs that were created in response to the pandemic. One of these programs, Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), extended eligibility of benefits to persons who otherwise would not have been covered by their regular state programs (e.g., gig workers), and the other, Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC), extended benefit durations beyond those provided by regular state programs.

As with FPUC, federal funding for these two additional programs ended in early September. Though certain states ended these three programs in June and July, eligible unemployed workers could still participate in their state’s regular jobless insurance program.Recipients of the regular state programs lost benefits upon reaching a maximum duration, which was in the range of 20 to 26 weeks for most states. There were a few other smaller programs in existence that we will not describe here, because these programs do not affect the broad analysis of this blog post.

Gauging the Response to Loss of Federal Benefits

Throughout the pandemic period, each state provided monthly reports that included the number of weeks of benefits paid on these programs. We used data from these reports to examine how the number of beneficiaries on all regular state programs changed when the $300 add-on disappeared.The data recorded the numbers of weeks that a person received benefits during a month; e.g., if a person received PUA benefits for four weeks in a month, their PUA benefits value would be four. We therefore approximated the number of monthly recipients of a particular UI program as the number of weeks paid divided by four. All else equal, the drop in participation in regular state programs is informative about how much the $300 add-on amplified the already present employment disincentive found in the regular program.

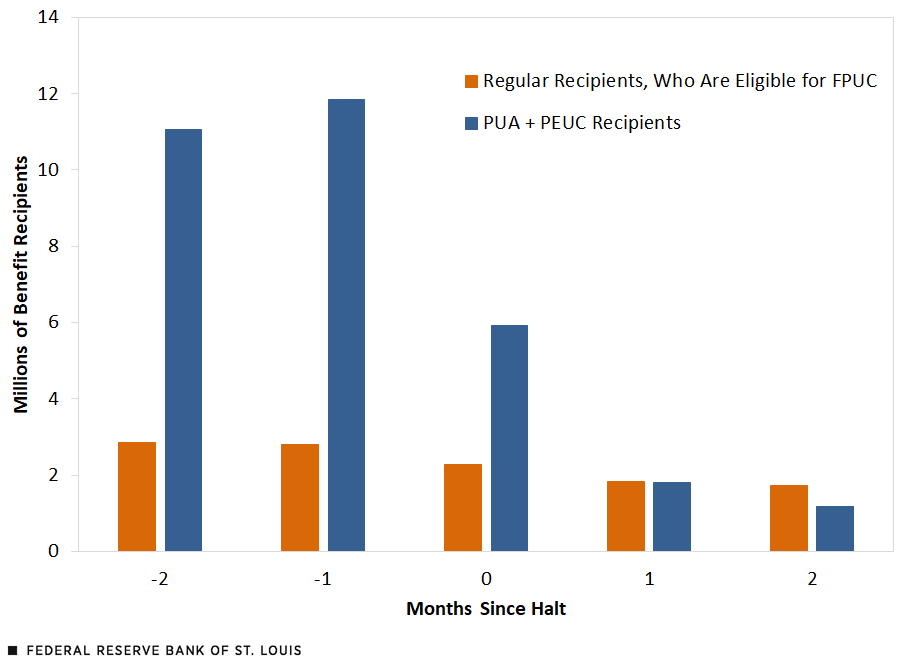

Since the end of benefits was asynchronous across states, we plotted the total regular state program recipients summed across all states (those that ended early and those that stopped in September) for the month FPUC ended as well as the months immediately before and after; these data are in orange, as shown in the figure below. In the month before cessation, about 2.8 million people collected regular state benefits. In the month after cessation, that amount fell to roughly 1.8 million people. Although this is a substantial decline, it suggests that a substantial fraction of recipients continued to collect unemployment benefits even though the benefits had declined by $300 per week as the result of the FPUC termination.

In blue, we plotted the total recipients on PUA and PEUC programs for the same five-month horizon interval. Before states halted PUA and PEUC, these programs made up about 80% of all recipients. After halting, the benefits paid out to PUA and PEUC programs reflected backpay from previous months when the programs were still in effect.

Change in Recipients with Halt of Key Federal Unemployment Programs

SOURCES: Bureau of Labor Statistics and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: FPUC=Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, PUA=Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, PEUC=Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation. Totals exclude Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and Vermont because of data unavailability.

Although the public focused on the $300 add-on as a key disincentive, the large drop in benefit recipients after pandemic unemployment benefits were halted was driven primarily by halting PUA and PEUC benefits. Continued analysis into the impact of halting pandemic unemployment benefits will provide valuable insight into the disincentive impact of unemployment benefits on employment.

Notes and References

- At first, the add-on provided $600 per week of additional benefits; this was passed as part of the CARES Act passed in March 2020. The program was renewed in December 2020 and modified such that the weekly add-on was reduced to $300 per week.

- Recipients of the regular state programs lost benefits upon reaching a maximum duration, which was in the range of 20 to 26 weeks for most states. There were a few other smaller programs in existence that we will not describe here, because these programs do not affect the broad analysis of this blog post.

- The data recorded the numbers of weeks that a person received benefits during a month; e.g., if a person received PUA benefits for four weeks in a month, their PUA benefits value would be four. We therefore approximated the number of monthly recipients of a particular UI program as the number of weeks paid divided by four.

Citation

Iris Arbogast and Bill Dupor, ldquoThe End of Emergency Pandemic Unemployment Benefits in 2021,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, April 7, 2022.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions