People Smooth Their Consumption. Shouldn’t Nations, Too?

According to mainstream economic theory, consumption should be less volatile than income. The reason is straightforward. If people lose their job and their income falls, they can tap their savings or take out a loan to cover their expenses. When they find a new job and income grows, the savings can be rebuilt or the loan repaid. That is, people can use their savings or borrowing to smooth their consumption over time.

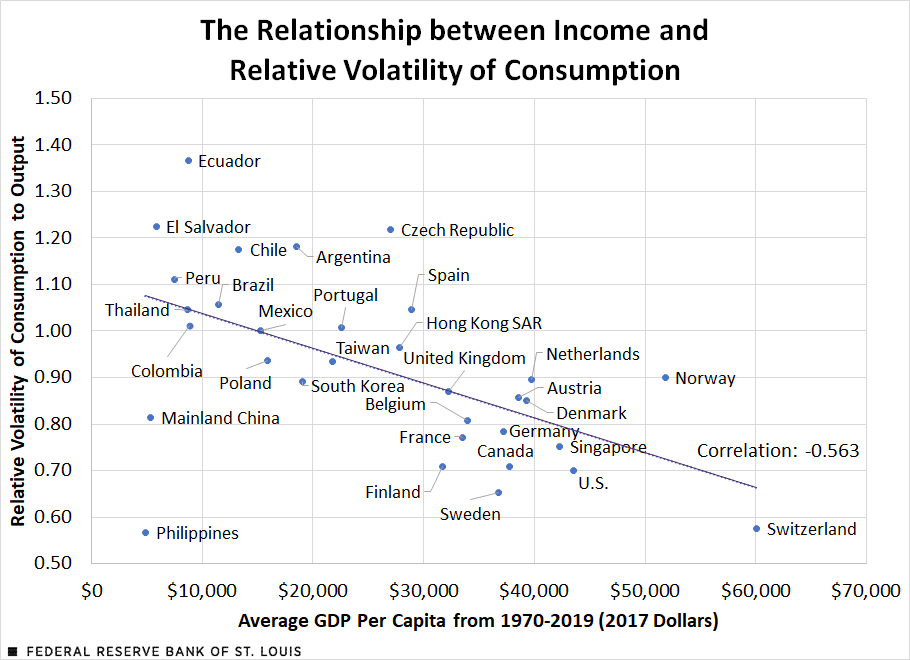

This should be true both for individuals and for the economy as a whole. Total consumption in an economy should be less volatile than that economy’s total income, or gross domestic product (GDP). But for many economies, that is not what we see. The vertical axis in the figure below measures the relative volatility of consumption to income in a sample of 32 advanced and emerging market economies. As shown in the figure, almost half the economies have a ratio greater than 1. That is, their consumption is more volatile than their income.

The horizontal axis of the figure measures the average income–average GDP—per person in each economy from 1970 to 2019. The purple line summarizes the negative relationship between them.The purple line shows the values of relative volatility predicted by GDP per capita.

SOURCES: Penn World Table version 10.0 and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: Relative volatility is the ratio of the standard deviation of the logarithmic difference of consumption to the standard deviation of the logarithmic difference of gross domestic product (GDP), calculated from 1970 to 2019. For example, a ratio greater than 1 means consumption is more volatile than income. The purple line shows the values of relative volatility predicted by GDP per capita.

In higher-income countries, consumption tends to be less volatile than income. In lower-income countries, consumption tends to be more volatile than income.The data are real (2017 dollars) and come from the Penn World Table version 10.0. Relative volatility is the ratio of the standard deviation of the logarithmic difference of consumption to the standard deviation of the logarithmic difference of GDP, calculated from 1970 to 2019.

Reasons for Higher Relative Volatility of Consumption

What explains the high relative volatility of consumption in lower-income countries? Here are some possibilities.

Measurement Error

Consumption is the most difficult category to measure on the expenditure side of the national accounts. In some low-income countries, consumption is measured as the residual after subtracting investment, government spending and net exports from GDP. The greater volatility of consumption in lower-income countries might reflect greater measurement error in the national accounts of these countries.

Durable Goods vs. Nondurable Goods and Services

Durable goods like cars and home appliances benefit their owners for many years. People buy durable goods infrequently and may delay purchases when income is temporarily low. Spending on nondurable goods (like food) and services (like health care) tends to be more frequent and harder to postpone. If durable goods are more important to consumers in lower-income countries, consumption would be more volatile.

Persistent Changes in Income

As described above, people should use savings or borrowing to smooth temporary fluctuations in income. If fluctuations in income are permanent, or if they predict future fluctuations in income, the predictions of mainstream economic theory change. Suppose an increase in income today predicts further increases in income in the future. People may want to enjoy the benefits of their future prosperity today. If so, they will borrow to increase their consumption by even more than the increase in their income.

Changes in Interest Rates

When interest rates change, people often change their saving or borrowing decisions. This makes their consumption change. If interest rates change more often than income or by large percentages, consumption can be more volatile than income.

This appears to be the case in some lower-income countries. Emerging market economies often face high and volatile interest rates due to fluctuations in credit risk. The fact that most of the countries with volatile consumption are open to international borrowing lends some support to the idea that changes in world interest rates play a role.

The Informal or Underground Economy

This explanation is an elaboration of the measurement error hypothesis. If a country has a large informal sector producing goods and services for consumers, and if this sector is not captured in the national accounts statistics, measured consumption can be volatile as people move their spending between formal and informal firms. If lower-income countries have larger informal sectors, their measured consumption could be more volatile.

So, out of all these alternative explanations, which one or which ones matter the most in explaining the observed excess volatility of consumption? We hope to have an answer soon as a result of our ongoing research on the topic.

Praew Grittayaphong, a research associate at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, provided research assistance.

Notes and References

- The purple line shows the values of relative volatility predicted by GDP per capita.

- The data are real (2017 dollars) and come from the Penn World Table version 10.0. Relative volatility is the ratio of the standard deviation of the logarithmic difference of consumption to the standard deviation of the logarithmic difference of GDP, calculated from 1970 to 2019.

Citation

Paulina Restrepo-Echavarría and Mark L.J. Wright, ldquoPeople Smooth Their Consumption. Shouldn’t Nations, Too?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 16, 2021.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions