North American Connectedness After NAFTA

The prevailing view among academics is that trade liberalization between countries leads to an increase in business cycle synchronization across countries.See, for example, Frankel, Jeffrey A.; and Rose, Andrew K. “The Endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Area Criteria.” The Economic Journal, July 1998, Vol. 108, Issue 449, pp. 1009-25; Baxter, Marianne; and Kouparitsas, Michael A. “Determinants of Business Cycle Comovement: A Robust Analysis.” Journal of Monetary Economics, January 2005, Vol. 52, Issue 1, pp. 113-57; and Kose, M. Ayhan; and Yi, Kei-Mu. “Can the Standard International Business Cycle Model Explain the Relation Between Trade and Comovement?” Journal of International Economics, March 2006, Vol. 68, Issue 2, pp. 267-95. Synchronization refers to increased similarity in the turning points of two countries’ business cycles. Business cycle synchronization is typically measured by the correlation between the two countries' GDP growth rates. Trade liberalization may increase GDP correlation through:

- Supply-side effects, such as linking the production sectors

- Demand-side effects

In the former case, an adverse shock to the importing country could affect the exporting country by reducing demand for intermediate goods (inputs for production). In the latter case, an adverse shock to the importing country could affect the exporting country by lowering demand for final goods (consumer goods).

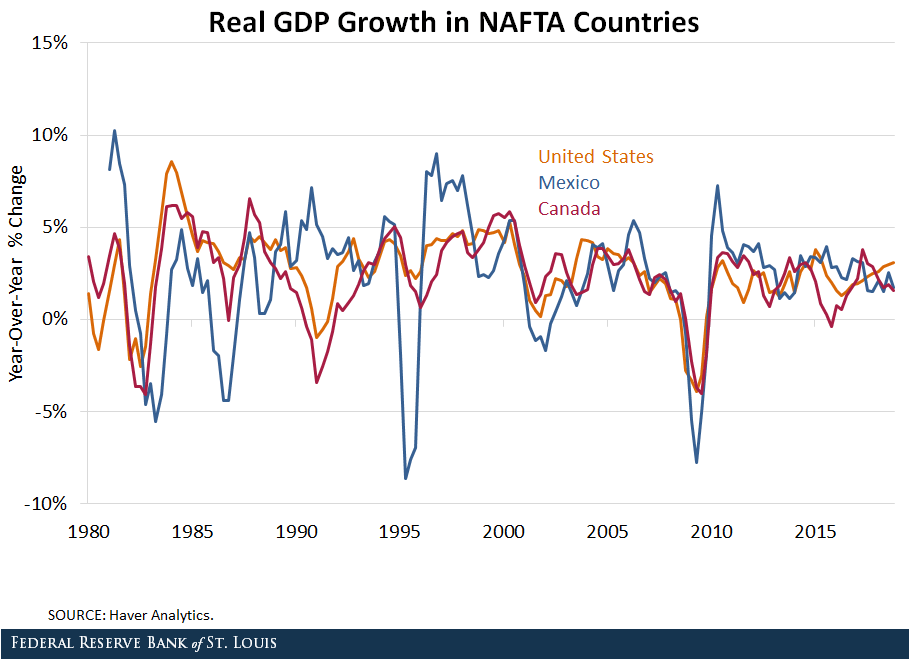

As an example, the figure below shows the GDP growth rates of Canada, Mexico and the U.S.

While many policies could have affected trade during the sample period, one important trade policy was the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), adopted in 1994.A number of studies have attempted to evaluate the effects of NAFTA. For example, see Burfisher, Mary E.; Robinson, Sherman; and Thierfelder, Karen. "The Impact of NAFTA on the United States." Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2001, Vol. 15, Issue 1, pp. 125-44; and Miles, William; and Vijverberg, Chu Ping C. “Mexico's Business Cycles and Synchronization with the USA in the Post NAFTA Years.” Review of Development Economics, November 2011, Vol. 15, Issue 4, pp. 638-50.

From 1990 to 2015, total trade volume among the three countries rose from $374 billion to $1.05 trillion, adjusted for inflation. A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that in 1990, before NAFTA, the GDP growth correlations between the U.S. and Canada, the U.S. and Mexico, and Mexico and Canada were 0.87, -0.02 and 0.12, respectively; in 2015, those correlations were 0.78, 0.63 and 0.54, respectively.

GDP Growth and Contagion

In a recent paper, we studied the effect of trade liberalization on the propagation of recessions across countries. Owyang, Michael T.; Piger, Jeremy; and Soques, Daniel. “Contagious Switching.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2019-014A, May 2019. Instead of focusing on the correlations between GDP growth rates, we examined how the increased probability of recession in one country impacts the probability of recession in other countries.

To analyze the transmission effects, we constructed an alternative measure of business cycle connectedness. Our measure computes the four-quarter cumulative increase in the foreign recession probability from a unit shock to the domestic economy when both countries are in an average expansion.

Before and After NAFTA

We found that the transmission effects of a recession in the U.S. were amplified after NAFTA. Prior to NAFTA, a shock that increased the probability of a U.S. recession from 10% to 90% raised the probability of recession over the next four quarters in Canada and Mexico by 1.38 and 0.27 percentage points, respectively.

After entering into NAFTA, the same increase in the U.S. recession probability raised the probability of recession over the next four quarters in Canada and Mexico by 8.24 and 7.59 percentage points, respectively.

Thus, for the case of NAFTA, trade liberalization increased business cycle synchronization across the three economies.

Notes and References

1 See, for example, Frankel, Jeffrey A.; and Rose, Andrew K. “The Endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Area Criteria.” The Economic Journal, July 1998, Vol. 108, Issue 449, pp. 1009-25; Baxter, Marianne; and Kouparitsas, Michael A. “Determinants of Business Cycle Comovement: A Robust Analysis.” Journal of Monetary Economics, January 2005, Vol. 52, Issue 1, pp. 113-57; and Kose, M. Ayhan; and Yi, Kei-Mu. “Can the Standard International Business Cycle Model Explain the Relation Between Trade and Comovement?” Journal of International Economics, March 2006, Vol. 68, Issue 2, pp. 267-95.

2 A number of studies have attempted to evaluate the effects of NAFTA. For example, see Burfisher, Mary E.; Robinson, Sherman; and Thierfelder, Karen. "The Impact of NAFTA on the United States." Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2001, Vol. 15, Issue 1, pp. 125-44; and Miles, William; and Vijverberg, Chu Ping C. “Mexico's Business Cycles and Synchronization with the USA in the Post NAFTA Years.” Review of Development Economics, November 2011, Vol. 15, Issue 4, pp. 638-50.

3 Owyang, Michael T.; Piger, Jeremy; and Soques, Daniel. “Contagious Switching.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2019-014A, May 2019.

Additional Resources

- Working Paper: Contagious Switching

- On the Economy: The U.S. Auto Labor Market since NAFTA

- On the Economy: Did NAFTA Shift Car Making to Other Countries?

Citation

Michael T. Owyang, Jeremy M Piger and Daniel Soques, ldquoNorth American Connectedness After NAFTA,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, May 27, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions