Staff Pick: Why Are Business Cycles in Emerging Economies More Volatile?

This blog will periodically rerun posts that were of particular interest. The following is a post by Fernando Leibovici from June 2018 discussing the role commodities play in volatile emerging market business cycles.

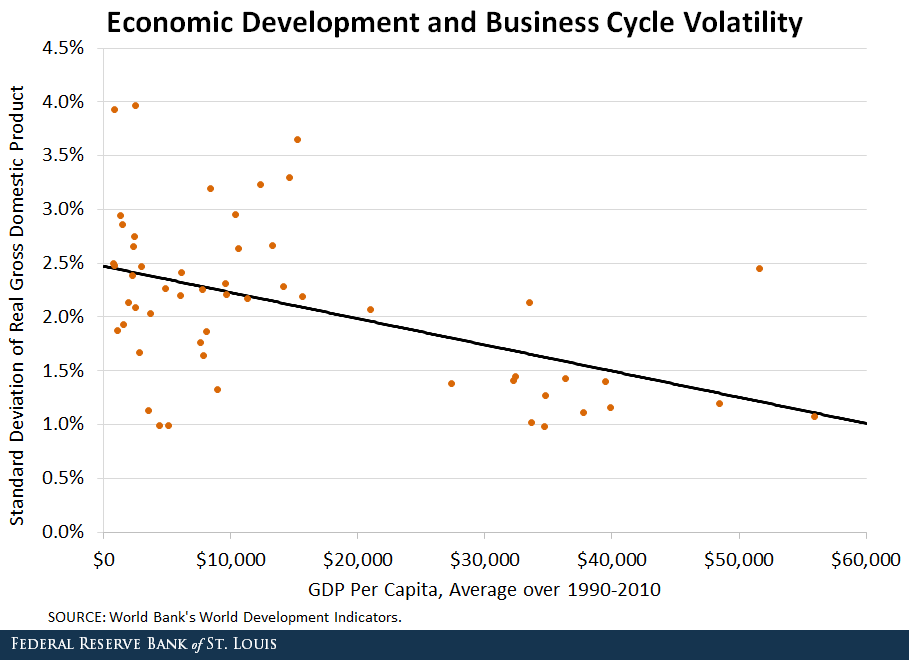

Business cycles in emerging economies are substantially more volatile than in developed ones, as illustrated in the figure below.

Understanding the forces that account for this is a fundamental and open question in international economics.

In our paper “Trade in Commodities and Business Cycle Volatility,”Kohn, David; Leibovici, Fernando; and Tretvoll, Håkon. “Trade in Commodities and Business Cycle Volatility.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2018-005A, March 2018. my co-authors, David Kohn and Håkon Tretvoll, and I studied the role of structural differences in the patterns of production and international trade between emerging and developed economies in accounting for the higher business cycle volatility of emerging economies.

Trade Composition: Emerging vs. Developed Economies

Our starting point was the observation that emerging economies produce and export systematically different goods than their developed counterparts while both types of economies import and consume very similar types of goods.

In particular, we documented that commodities make up 71 percent of aggregate exports and 33 percent of aggregate imports in the average emerging economy.We followed Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé and Martin Uribe’s 2017 paper “How Important Are Terms-of-Trade Shocks?” in classifying countries. Countries with average GDP per capita below $25,000 over the period 1990-2010 were classified as “emerging,” while the rest were denominated as “developed.” GDP per capita was adjusted by using purchasing power parity to convert the value into 2005 dollars. In contrast, the shares of commodities in aggregate exports and imports for the average developed economy are very similar to each other at 29 percent and 31 percent, respectively.

That is, while emerging economies produce more commodities than they consume, developed economies produce and consume commodities in similar amounts.

International Relative Prices Affect Economic Activity in Emerging Economies

In our paper, we used an economic model to show that these systematic differences between emerging and developed economies affect their responses to changes in the international price of commodities relative to manufactures, amplifying business cycle volatility in emerging economies.

Consider, for instance, an increase in the relative price of commodities. In emerging economies, the share of commodities in total production is larger than their share in total consumption. Thus, an increase in the relative price of commodities increases the value of the type of goods produced relative to those consumed, triggering an economic boom.

In our model, the higher value of commodities increases the amount of resources available to accumulate capital and increase consumption and also increases the returns to capital accumulation and labor hiring. In addition, there is an increase in aggregate productivity as production inputs are reallocated across sectors.

In contrast, the share of commodities in production and consumption is much more similar in developed economies. Thus, changes in the relative price of commodities have a small impact on the relative value of production and, therefore, a minor impact on aggregate economic activity.

Quantitative Findings

Our model implies that these effects are quantitatively important: Systematic differences in the patterns of production and trade between emerging and developed economies accounted for 52 percent of the difference in average volatility across these economies.

We then showed that our explanation is consistent with evidence from cross-country data.

First, we documented that sectoral imbalances in the trade of commodities and manufactures—a salient feature of emerging economies—are positively correlated with business cycle volatility. This is true even after controlling for a country’s level of economic development and other cross-sectional features of their patterns of trade and production.

Second, we showed that our model can account for a significant fraction of the country-by-country relationship between business cycle volatility and the cross-sectional characteristics examined in the empirical analysis.

Conclusion

These findings show that structural differences in the patterns of production and trade between emerging and developed economies are important in accounting for the higher business cycle volatility of emerging economies.

This mechanism complements others previously studied in the literature, ranging from differences in institutional quality, financial development or the effectiveness of public policy, to differences in the magnitude and persistence of the shocks faced by these economies.

Notes and References

1 Kohn, David; Leibovici, Fernando; and Tretvoll, Håkon. “Trade in Commodities and Business Cycle Volatility.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2018-005A, March 2018.

2 We followed Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé and Martin Uribe’s 2017 paper “How Important Are Terms-of-Trade Shocks?” in classifying countries. Countries with average GDP per capita below $25,000 over the period 1990-2010 were classified as “emerging,” while the rest were denominated as “developed.” GDP per capita was adjusted by using purchasing power parity to convert the value into 2005 dollars.

Additional Resources

- Working Paper: Trade in Commodities and Business Cycle Volatility

- On the Economy: The Evolution of US Agricultural Exports

- On the Economy: The Economic Impact of Terrorism on Developing Countries

Citation

ldquoStaff Pick: Why Are Business Cycles in Emerging Economies More Volatile?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Jan. 7, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions