Why Medicaid Eligibility Impacts Savings

In a previous blog post, we discussed how eligibility for Medicaid affects the savings decisions of low-income families, particularly among financially stressed households.

Low-income families that are the most financially stressed plan to save, or pay down debt, with a larger share of their tax refund once they become eligible for medical coverage under Medicaid, according to analysis of data by the Center for Household Financial Stability at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the Center for Social Development and Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis.

In contrast, eligibility seems to make no difference in savings rates for the average low-income household that is not financially stressed.

This post explores the reasons why being eligible for Medicaid would lead to different savings responses. Several competing forces may account for the difference, author Emily Gallagher pointed out in a recent edition of In the Balance.

In the article, Gallagher, who is a visiting scholar at the St. Louis Fed’s Center for Household Financial Stability, highlighted her recent working paperSabat, Jorge; Gallagher, Emily; Gopalan, Radhakrishnan; and Grinstein-Weiss, Michal. “Medicaid and Household Savings Behavior: New Evidence from Tax Refunds.” Dec. 4, 2017. with co-authors Radhakrishnan Gopalan, Michal Grinstein-Weiss and Jorge Sabat.

Particularly, she identified three possible reasons why Medicaid affects savings:

- The use of bankruptcy as a way to manage medical bills.

- A desire on the part of uninsured households to save for future health events.

- The impression that one’s Medicaid access is often transient.

Bankruptcy as a De Facto Health Plan

One reason eligibility might boost the savings of low-income families is that Medicaid offers them a reason to save. “Households rest assured that they can hold onto their savings even if they are hit with a health problem because the medical bills won’t push them into bankruptcy,” Gallagher wrote.

In other words, Medicaid gives hope to families who otherwise worry about keeping up with their bills, she said. Low-income households who file for bankruptcy could lose everything they have saved to cover future medical bills.

In a sense, she noted, bankruptcy acts for some households as a high deductible health plan. “The deductible is proportional to how much the household has saved at the moment of bankruptcy,” the article said. “In that role, bankruptcy might reduce household savings rates,” Gallagher wrote. “Among financially distressed households, the increase in savings under Medicaid may reflect a reduced necessity to resort to bankruptcy.”

Consistent with this explanation, she noted that Medicaid has more than twice the positive effect on the propensity to save from tax refunds in states where households tend to be forced to hand over more of their savings in a bankruptcy.

Saving for Future Health Events?

Another possible explanation for the different savings responses has to do with incentives to save as a form of self-insurance against large medical expenses.

“Knowing that future medical bills will be covered frees up those doing comparatively better to repair their cars or buy school clothes for the kids,” Gallagher wrote. “Households that are not in financial distress may, therefore, save less when gaining access to Medicaid.”

However, the evidence does not seem to support this possible explanation. “On average, households that are not in financial distress do not reduce their savings when they become eligible for Medicaid,” Gallagher wrote.

Shaky Medicaid Access Is Linked to More Saving

A more likely explanation for the different savings responses among low-income households is due to the transient nature of Medicaid access for some households, she noted.

“Fluctuations in monthly income combined with frequent income verification by program administrators cause some households to qualify for Medicaid in some months but not in others,” Gallagher explained. She added that, by some estimates, more than 30 percent of households lose eligibility within six months of enrollment.Sommers, Benjamin D.; and Rosenbaum, Sara. “Issues in Health Reform: How Changes in Eligibility May Move Millions Back and Forth between Medicaid and Insurance Exchanges.” Health Affairs, February 2011, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 228-36. Swartz, Katherine; Short, Patricia Farley; Graefe, Deborah Roempke; and Uberoi, Namrata. “Evaluating State Options for Reducing Medicaid Churning.” Health Affairs, July 2015, Vol. 34, No. 7, pp. 1180-7.

Gallagher pointed out that Medicaid access is likely to be perceived as transient by households that have a low probability of eligibility to begin with, such as households in states with a very low income-eligibility limit or members of demographic groups that have a relatively high average income. Even a small change in either rules or income might be sufficient to end their access, she said.

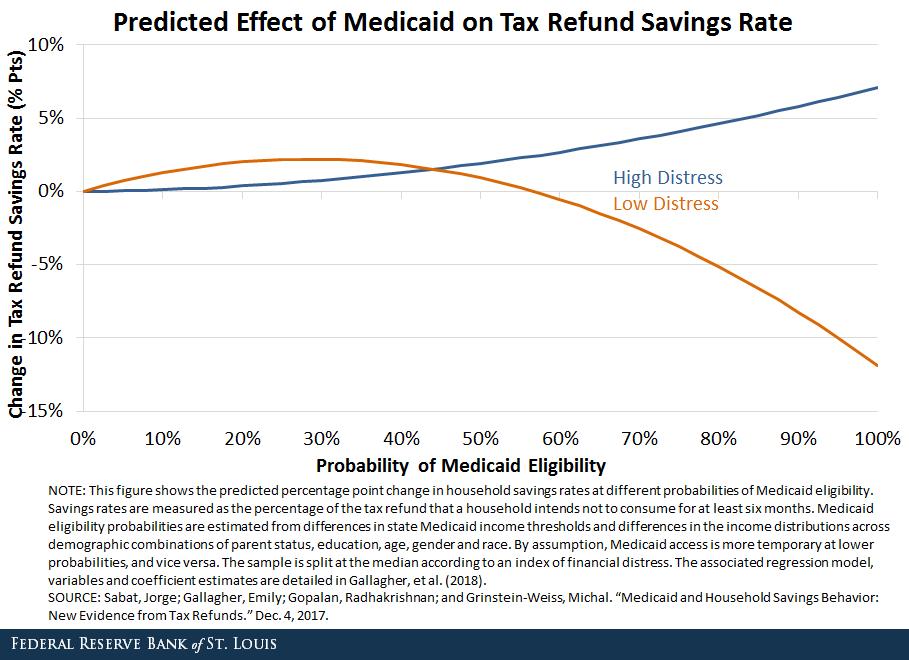

Consistent with this expectation, having a low probability of Medicaid access is associated with modestly higher savings among households with low financial distress, as shown below. “In particular, a household with a 20 percent probability of Medicaid access saves about 2 percentage points more of its refund than a similar household with no chance at Medicaid,” Gallagher said.

In contrast, households with low financial distress and a high probability of Medicaid eligibility have a substantial negative savings response to gaining access. “For example, at an 80 percent simulated probability of Medicaid eligibility, the savings rate is 5 percentage points below that of a similar household without Medicaid access,” she wrote.

When households with low financial distress are taken together, she noted that these two opposing responses wash out on average.

Meanwhile, for households that are financially distressed, the predicted response in saving is always positive and increases with the likelihood of Medicaid access, consistent with Medicaid obviating the role of bankruptcy as de facto health plan, Gallagher noted.

Notes and References

1 Sabat, Jorge; Gallagher, Emily; Gopalan, Radhakrishnan; and Grinstein-Weiss, Michal. “Medicaid and Household Savings Behavior: New Evidence from Tax Refunds.” Dec. 4, 2017.

2 Sommers, Benjamin D.; and Rosenbaum, Sara. “Issues in Health Reform: How Changes in Eligibility May Move Millions Back and Forth between Medicaid and Insurance Exchanges.” Health Affairs, February 2011, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 228-36. Swartz, Katherine; Short, Patricia Farley; Graefe, Deborah Roempke; and Uberoi, Namrata. “Evaluating State Options for Reducing Medicaid Churning.” Health Affairs, July 2015, Vol. 34, No. 7, pp. 1180-7.

Additional Resources

Citation

ldquoWhy Medicaid Eligibility Impacts Savings,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Dec. 13, 2018.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions