The State of U.S. Household Wealth

The State of U.S. Household WealthThe State of U.S. Household Wealth was updated quarterly from 2020, when it was launched as the Real State of Family Wealth, through the end of 2024. For related research and resources, see featured publications from our Community Development team. provides a look at average, inflation-adjusted wealth for various groups. Research on wealth distribution in the U.S., along with outreach and engagement in communities, helps the St. Louis Fed better understand current financial conditions and how the macroeconomic environment and household-level finances may be related.

The following analysis presents quarterly data on the distribution of average household wealth by generation, education and race.Average wealth estimates are much higher than median wealth estimates and therefore are more representative of wealthier households’ experiences. However, median (i.e., the middle of the distribution) data on household wealth aren’t available on a quarterly basis. Knowing the distribution of wealth over time is important for understanding how and why U.S. household wealth fluctuates, as well as for promoting economic resilience and mobility in low- and moderate-income and underserved communities.

Key Takeaways

For the fourth quarter of 2024 (through Dec. 31):

How is wealth distributed among U.S. households? By household income?

- The top 10% of households by wealth had $8.1 million on average. As a group, they held 67.2% of total household wealth.

- The bottom 50% of households by wealth had $60,000 on average. As a group, they held 2.5% of total household wealth.

- The top 20% of households by income had $4.3 million in wealth on average. As a group, they held 71.1% of total household wealth.

- The bottom 20% of households by income had $180,000 in wealth on average. As a group, they held 3% of total household wealth.

What is the current distribution of U.S. wealth by generation?

- Younger Americans (millennials and Gen Zers) owned $1.23 for every $1 of wealth owned by Gen Xers at the same age.Wealth holdings of younger Americans are for households headed by someone born in 1981 or later. This group comprises households from two generations: millennials and Gen Zers. Returning readers may notice that quarterly estimates of average wealth published before the third quarter of 2023 showed that younger Americans had lower wealth than older generations at similar ages. A Survey of Consumer Finances data release in October 2023 resulted in significant backward revisions in the Distributional Financial Accounts, and updated estimates of the wealth levels of younger Americans were significantly higher than prior estimates. Our currently published estimates take this into account. See the methodology section for greater details regarding the Distributional Financial Accounts.

- Younger Americans (millennials and Gen Zers) owned $1.35 for every $1 of wealth owned by baby boomers at the same age.

What is the current distribution of U.S. wealth by household education?

- Households headed by someone with some college education (but no four-year degree) had 30 cents for every $1 of wealth held by households headed by a four-year college graduate.

- Households headed by someone with a high school diploma had 22 cents for every $1 of wealth held by households headed by a four-year college graduate.

- Households headed by someone with less than a high school diploma had 9 cents for every $1 of wealth held by households headed by a four-year college graduate.

What is the current distribution of U.S. wealth by race?

- Black households had about $352,000 in average wealth, a 53% increase since the end of the Great Recession.

- Hispanic households had about $285,000 in average wealth, a 63% increase since the end of the Great Recession.

- White households had about $1.5 million in average wealth, a 68% increase since the end of the Great Recession.

Despite increased volatility in wealth levels, average wealth grew for all groups over the past five years (including during the COVID-19 pandemic). Wealth gains partially eroded in 2022 as economic headwinds (e.g., inflation, the expiration of pandemic-related support) put pressure on household finances. That said, average wealth outcomes as of the fourth quarter of 2024 remain elevated relative to prepandemic levels.

To visualize these data in detail, click on the headings below.

Figures and data show average household wealth by generation: baby boomers, Gen Xers and millennials/Gen Zers.

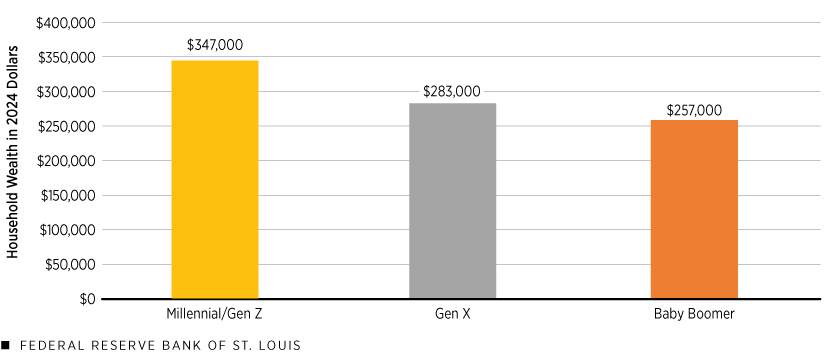

Younger Americans (millennials and Gen Zers, or those born in 1981 or later) had greater household wealth, on average, than Gen Xers (born between 1965 and 1980) and baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) did when both generations were close to the same average age (34).See Endnote 3 for why this estimate of younger Americans’ wealth is now significantly higher than estimates published before the third quarter of 2023. In the fourth quarter of 2024, younger Americans owned $1.23 for every $1 of wealth owned by Gen Xers, on average, at close to the same age (2007:Q1). Younger Americans owned $1.35 for every $1 of wealth owned by baby boomers, on average, at close to the same age (1989:Q3).

Average Wealth at Age 34 by Generation

SOURCES: Distributional Financial Accounts and Community Development Research calculations.

NOTES: Values are rounded to the nearest $1,000 and calculated when each generation was relatively young. The data are based on the quarter and year when the generation’s average age was about 34: baby boomers, 1989:Q3; Gen Xers, 2007:Q1; and millennials/Gen Zers, 2024:Q4.

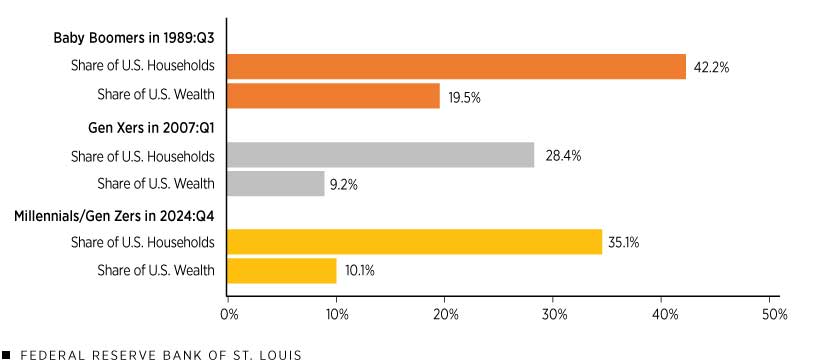

When households are younger, they tend to have lower levels of wealth. To address this issue, we compared household and wealth shares across generations when their members were relatively young (at an average age of 34).

As the following figure shows, each generational group owned less wealth than their share of the household population. Baby boomers represented 42.2% of households in the third quarter of 1989, yet they owned only 19.5% of total household wealth in 1989; this is 54% less wealth than their representation among U.S. households might predict. Gen X households accounted for 28.4% of U.S. households and owned 9.2% of total household wealth (68% less wealth given their household share) in 2007. Younger American (millennial and Gen Z) households represented 35.1% of U.S. households and owned 10.1% of total household wealth (71% less wealth given their household share) in 2024. The baby boomers’ shortfall was the smallest of the generations.

Generational Shares of U.S. Households and Wealth at Same Age

SOURCES: Distributional Financial Accounts and Community Development Research calculations.

NOTES: Shares are calculated when each generation was relatively young (at an average age of 34). The data are for the quarter in the year when the generation was at that average age.

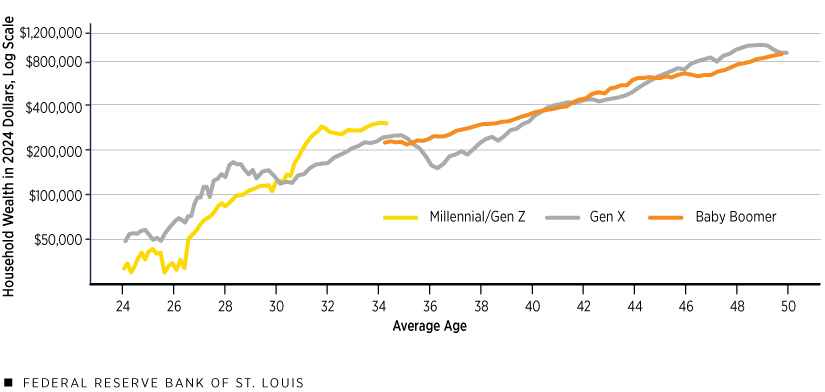

The figure below shows the average, inflation-adjusted household wealth of the three generations during their young- to mid-adult years. Values are centered on the average age of the generation, based on the age of the reference person within households. For example, the average age of younger Americans (millennials and Gen Zers) in the fourth quarter of 2024 was about 34, and Gen Xers had a similar age in the first quarter of 2007.

Average Wealth by Generation

SOURCES: Distributional Financial Accounts and Community Development Research calculations.

While trailing Gen Xers for the beginning of their adult lives, younger American households’ average wealth began to exceed that of Gen Xers at about age 30, reflecting historically high wealth levels following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Between ages 34 and 50, the average wealth held by Gen Xers and baby boomers crosses various times, which is also indicative of larger macroeconomic forces. For example, in 2006 Gen Xers’ average wealth was higher than that of baby boomers in 1989, but it fell sharply during the 2007-09 Great Recession and took years to recover.

Figures and data show average household wealth by level of completed education: no high school diploma, high school diploma, some college, and at least a four-year college degree.

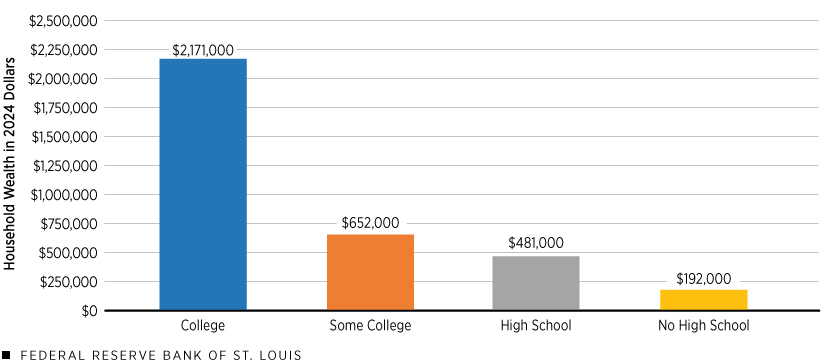

The following figure shows the average, inflation-adjusted wealth for households by education level in the fourth quarter of 2024. Households headed by someone with some college education (but no four-year degree) had 30 cents in wealth for every $1 of wealth held by households headed by a college graduate. Those with a high school diploma owned 22 cents for every $1 of college-graduate wealth, and those with less than a high school diploma had 9 cents for every $1.

Average Wealth by Education, Fourth Quarter of 2024

SOURCES: Distributional Financial Accounts and Community Development Research calculations.

NOTES: Values have been rounded to the nearest $1,000. College represents households with at least a bachelor’s degree; other education levels represent households’ highest completed education.

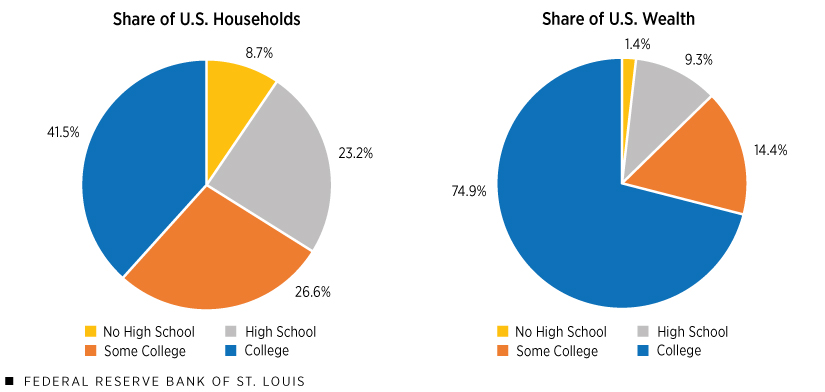

In the fourth quarter of 2024, households headed by a college graduate owned the disproportionately highest share of total household wealth. (See the figure below.) They owned 74.9% of total household wealth despite making up only 41.5% of households, an advantage of 80% greater wealth than we might expect based on their household representation. Households headed by someone with some college education but no degree, those with at most a high school diploma, and those with less than a high school diploma collectively owned 46%, 60% and 84% less wealth, respectively, than we might expect based on their household representation.

Distribution of U.S. Households and Wealth by Education, Fourth Quarter of 2024

SOURCES: Distributional Financial Accounts and Community Development Research calculations.

NOTE: College represents households with at least a bachelor’s degree; other education levels represent households’ highest completed education.

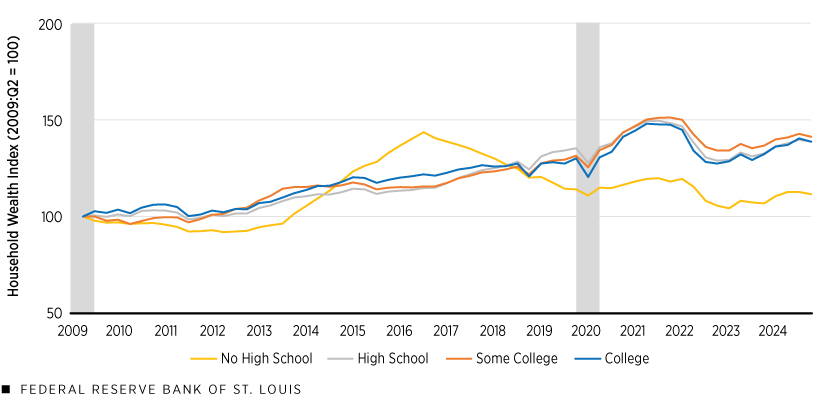

The next figure shows cumulative changes in the average, inflation-adjusted wealth of households with a given educational attainment over time. On average, all households have greater wealth than similarly educated households did after the Great Recession ended in 2009. In the fourth quarter of 2024, the wealth of households with a college degree was 39% greater on average than similar households in 2009 (increasing from about $1.6 million to about $2.2 million).These percentages are calculated using unrounded numbers and thus may differ slightly from calculations made using rounded numbers available in the text.

Cumulative Changes in Average Wealth by Education

SOURCES: Distributional Financial Accounts and Community Development Research calculations.

NOTES: College represents households with at least a bachelor’s degree; other education levels represent households’ highest completed education. Vertical bars indicate recessions. Wealth was inflation-adjusted to 2024 dollars.

In contrast, households with some college had 41% more wealth (increasing from $461,000 to $652,000), and those with just a high school diploma had 39% more wealth than similar households had in 2009 (increasing from $346,000 to $481,000). The least educated group, those without a high school diploma, had 12% more wealth than they had in 2009 (increasing from $172,000 to $192,000).Again, these percentages are calculated using unrounded numbers and thus may differ slightly from calculations made using rounded numbers available in the text. The difference in the dollar values of those gains reflect the underlying educational wealth gap, a gap that has expanded considerably over the past few decades.

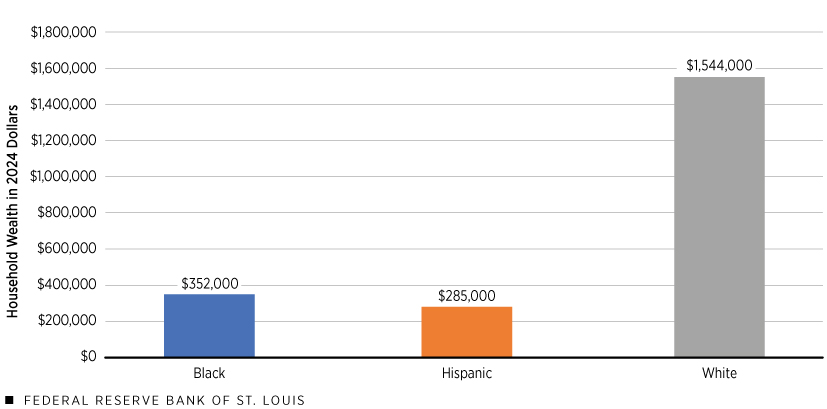

Figures and data show average wealth for Black, Hispanic and white households.

The following figure shows the average, inflation-adjusted wealth for Black, Hispanic and white households in the fourth quarter of 2024.The Federal Reserve Board’s Distributional Financial Accounts groups households based on the primary race/ethnicity of the survey respondent. Groups in the public dataset are mutually exclusive. The question on race includes white, Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino as options. In the public dataset, the remainder of respondents are grouped into a diverse “other or multiple races” group, which includes Asians, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, other races and multiple racial identifications. Because the diversity of this category of other or multiple races potentially masks great intragroup wealth variation, it is not a focus of The State of U.S. Household Wealth. Black households had wealth of about $352,000, Hispanic households had wealth of about $285,000, and white households had wealth of about $1.5 million.

Average Wealth by Primary Race or Ethnicity, Fourth Quarter of 2024

SOURCES: Distributional Financial Accounts and Community Development Research calculations.

NOTE: Values have been rounded to the nearest $1,000.

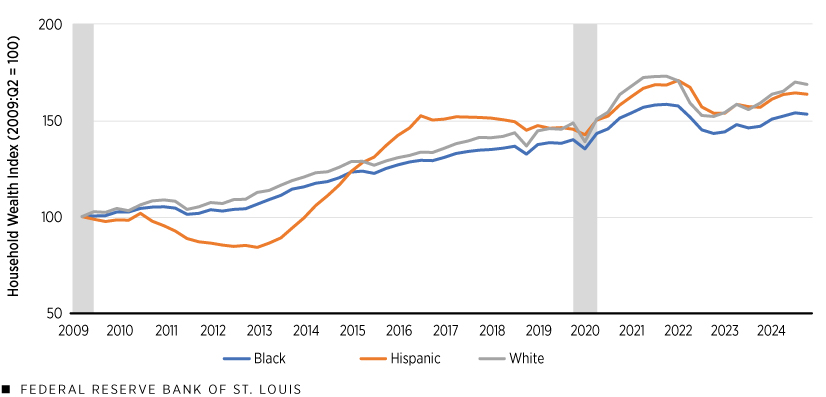

Since the end of the Great Recession in 2009, white household wealth and Black household wealth have followed similar growth trends, with the growth in white household wealth being slightly steeper, on average. (See the figure below.) Hispanic household wealth, however, fell for several years before recovering rapidly. Despite large declines over the course of 2022, average wealth for all groups was higher in 2024 than it was when the COVID-19 pandemic began.

Cumulative Changes in Average Wealth by Race and Ethnicity

SOURCES: Distributional Financial Accounts and Community Development Research calculations.

NOTES: Vertical bars indicate recessions. Wealth was inflation-adjusted to 2024 dollars.

Since the end of 2022, wealth levels across groups generally have increased. Overall, white household average wealth grew 68%, from $918,000 to about $1.5 million, since the end of the Great Recession; Black household average wealth grew 53%, from $231,000 to $352,000; and Hispanic household average wealth grew 63%, from $175,000 to $285,000.See Endnote 6; unrounded numbers were used to calculate these percentages.

- The State of U.S. Household Wealth was updated quarterly from 2020, when it was launched as the Real State of Family Wealth, through the end of 2024. For related research and resources, see featured publications from our Community Development team.

- Average wealth estimates are much higher than median wealth estimates and therefore are more representative of wealthier households’ experiences. However, median (i.e., the middle of the distribution) data on household wealth aren’t available on a quarterly basis.

- Wealth holdings of younger Americans are for households headed by someone born in 1981 or later. This group comprises households from two generations: millennials and Gen Zers. Returning readers may notice that quarterly estimates of average wealth published before the third quarter of 2023 showed that younger Americans had lower wealth than older generations at similar ages. A Survey of Consumer Finances data release in October 2023 resulted in significant backward revisions in the Distributional Financial Accounts, and updated estimates of the wealth levels of younger Americans were significantly higher than prior estimates. Our currently published estimates take this into account. See the methodology section for greater details regarding the Distributional Financial Accounts.

- See Endnote 3 for why this estimate of younger Americans’ wealth is now significantly higher than estimates published before the third quarter of 2023.

- These percentages are calculated using unrounded numbers and thus may differ slightly from calculations made using rounded numbers available in the text.

- Again, these percentages are calculated using unrounded numbers and thus may differ slightly from calculations made using rounded numbers available in the text.

- The Federal Reserve Board’s Distributional Financial Accounts groups households based on the primary race/ethnicity of the survey respondent. Groups in the public dataset are mutually exclusive. The question on race includes white, Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino as options. In the public dataset, the remainder of respondents are grouped into a diverse “other or multiple races” group, which includes Asians, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, other races and multiple racial identifications. Because the diversity of this category of other or multiple races potentially masks great intragroup wealth variation, it is not a focus of The State of U.S. Household Wealth.

- See Endnote 6; unrounded numbers were used to calculate these percentages.

The State of U.S. Household Wealth is produced by researchers in the St. Louis Fed’s Community Development department. We use the Federal Reserve Board’s Distributional Financial Accounts (DFAs) as our dataset, which provides quarterly estimates of nominal, aggregate U.S. household wealth. Wealth, or net worth, is defined as the sum of assets less liabilities. We make two important adjustments to the DFAs:

- We adjust for inflation using the consumer price index, yielding household wealth values in real terms. This adjusts for changes in the purchasing power of a dollar over time.

- We also adjust for household population. This allows us to account for changing group sizes and to express wealth in terms of the average household’s household finances.

The result is average, inflation-adjusted household wealth values, available from 1989 onward on a quarterly basis.

The State of U.S. Household Wealth supplements other Community Development research that generally uses median wealth instead of average wealth, producing different estimates of generational, educational and racial wealth gaps.

The Federal Reserve Board creates the DFAs by combining data from the triennial Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) and the quarterly Financial Accounts of the United States. See a paper by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System for a discussion of how the estimates are constructed. Many of our reports use the SCF instead of the DFAs. The SCF is an extensive survey that allows us to examine median household wealth (wealth at the middle, or 50th, percentile). Because of how wealth is distributed, average wealth estimates tend to be much higher than median wealth estimates. We believe median household wealth is more representative of a demographic group’s typical economic experience than average household wealth. However, the SCF is released only every three years, with the most recent survey featuring 2022 data.

While we prefer the depth of information provided by SCF data, the DFAs allow us to study wealth trends in a timelier fashion, though with less flexibility than the SCF and an inability to examine median household wealth. Because specific DFA estimates change from quarter to quarter as data are updated, we advise placing more weight on trends than on specific values. Overall, as average wealth trends roughly track median wealth trends, we find low levels of wealth and wealth gaps among underserved populations using both the SCF and DFAs.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us