Three Reasons Why Millennials May Face Devastating Setback from COVID-19

Millennials are known for many things: avocado toast, craft beer, striving for work-life balance and valuing experiences above material things. Recently, this generation has also become known for its financial struggles in the wake of the Great Recession.

And that was before the coronavirus pandemic. While national crises like this one hit all generations, I believe there are three reasons why many millennials (those born between 1981 and 1996) may be hit particularly hard.

Will the typical millennial have to further delay major saving goals, including a home purchase, college tuition (for themselves or their children) and retirement? In other words, will this double-blow—Great Recession + Pandemic—be a devastating setback? For some millennials, particularly those who are more financially vulnerable, it seems a real possibility.

1. Still Reeling from the Great Recession

Most generations had seen some financial improvement a decade after the start of the Great Recession. Not so true for older millennials (those born in the 1980s), who were the only generation to have fallen further behind between 2010 and 2016. This prompted my colleagues at the Center for Household Financial Stability and myself to wonder if they would become a “lost generation” financially who struggled to achieve saving milestones.

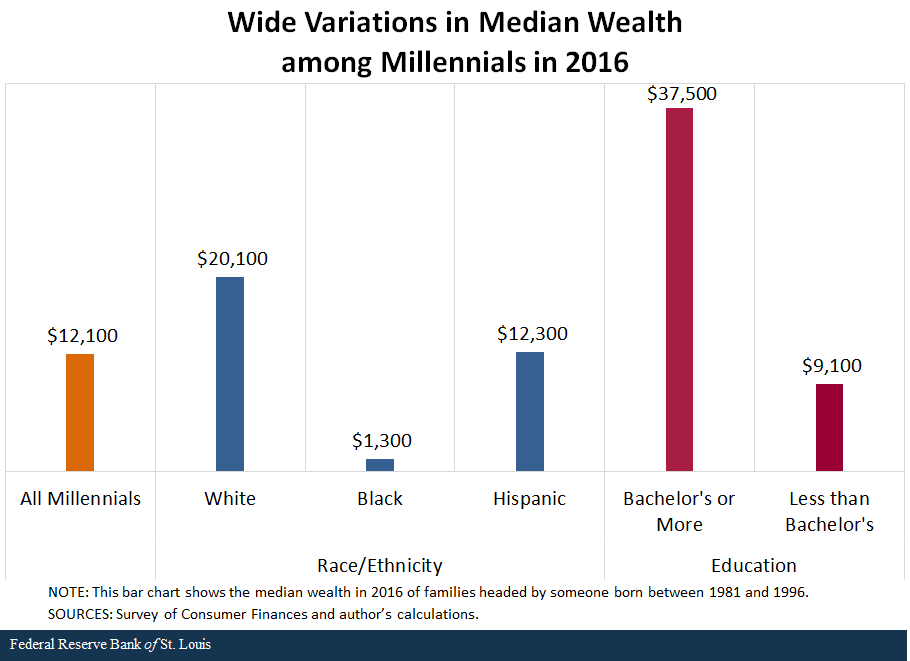

This has become a likelier possibility today, as many millennials were still reeling from the blow of the last recession when COVID-19 hit. The figure below highlights median wealth (i.e., at the middle) for millennial families (born between 1981 and 1996) using the most up-to-date data. Shown from left to right, the wealth levels are for all millennials; for whites, blacks and Hispanics; and for those with a bachelor’s degree or more and those with less than a bachelor’s degree.

2. Little to No Financial Buffer

Recent data Findings presented here use data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking, and the Distributional Financial Accounts from the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors, as well as from the IPUMS-Current Population Survey. further highlight millennials’ vulnerability. In the fourth quarter of 2019, they had a smaller share of total household wealth compared with older generations at similar ages. That time marked the final quarter of a record economic expansion. If millennials as a group were still behind and struggling financially after so many years of overall growth, a large economic shock (like the one caused by COVID-19) could upend many of their lives.

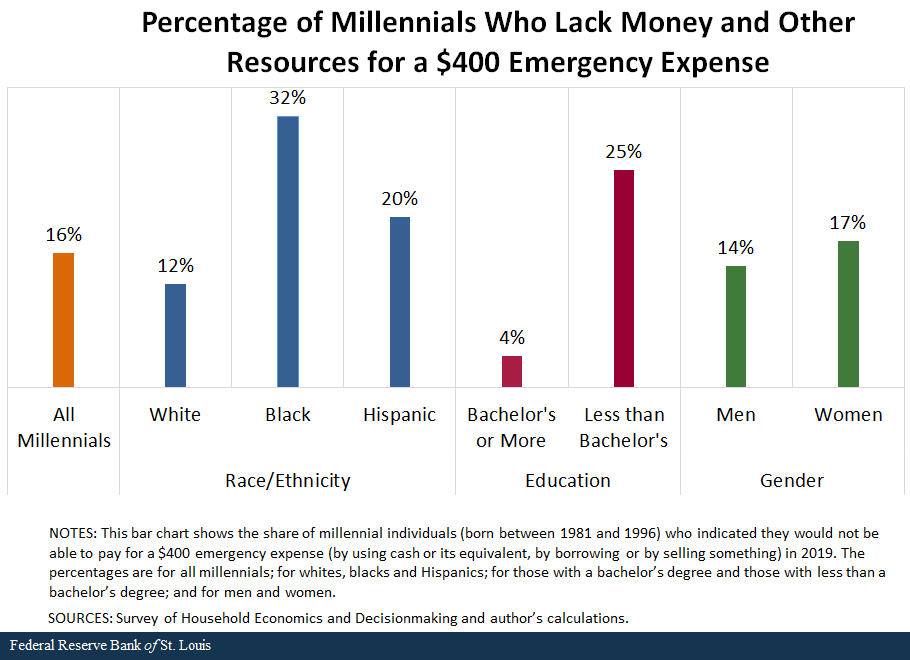

Financial difficulty in the event of income loss is more likely if the family doesn’t have a wealth buffer or cash on hand to withstand financial disruption. For millennial families, the lack of a financial buffer is disturbingly common, as can be seen in the figure below. About 1 in 4 families have negative net worth, meaning their debts outsize their assets. And roughly 1 in 6 say they would be completely unable to pay for a $400 emergency expense (i.e., not with cash, credit cards, borrowing or selling assets). In 2019, 63% of Americans reported they would pay for a $400 emergency expense with cash or its equivalent. Of the remainder, the majority said they would meet this expense in other ways. Only 12% of Americans reported they would not be able to pay the emergency expense at all. For those experiencing job loss, these emergencies can prove catastrophic without sufficient financial cushion.

3) Sizeable Job Loss (and Thus Income Loss)

A third reason for millennials’ vulnerability: Many of the individuals who have lost their jobs are younger. About 5,556,000 millennials (not seasonally-adjusted) I use the Current Population Survey unemployment numbers that have not been adjusted for seasonality; doing so would increase these numbers. These numbers are also not directly comparable with initial jobless claims, which is a gross, not net, measure of job loss. See this New York Fed blog post. joined the unemployed between February and April 2020. Employees in the hard-hit leisure and hospitality industry also tend to be younger on average.

Many of the recently unemployed millennials are the same young people who likely have fewer savings and wealth to fall back on when they lose their incomes, as explored above. But even within the millennial group, some individuals and families are more likely than others to struggle.

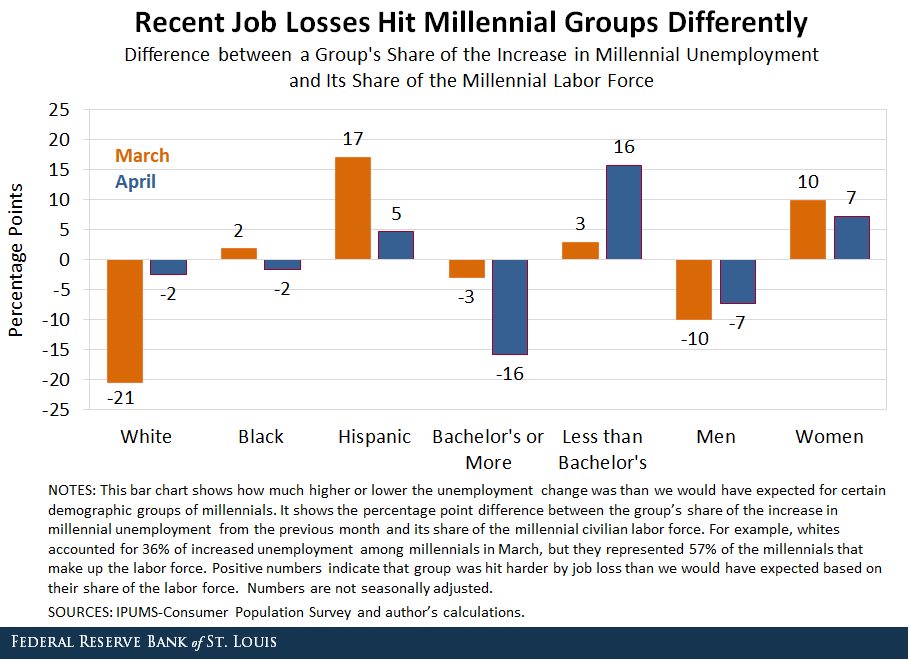

Past research from our center and elsewhere has found that blacks, Hispanics, those without four-year college degrees and women were more likely to be struggling financially than their counterparts. These same demographic groups were also hit harder in terms of job loss in March and again in April, as can be seen in the figure below.

To measure how growing unemployment affected different groups of millennials, I took the difference between the particular group’s share of the increase in millennial unemployment and that group’s share of the millennial civilian labor force. For example, whites accounted for 36% of increased unemployment among millennials in March, but they represented 57% of the millennials that make up the labor force; as result, the percentage point difference is -21. Positive bars indicate those groups' job losses outsized their share of the labor force.

We can see that Hispanics were particularly hard-hit in the early, first round of job loss in March, with a 17 percentage point difference, and less educated millennials were harder hit in the second, larger round of job loss in April, with a 16 percentage point difference.

Many in these hard-hit groups also had less wealth and little to no financial buffer to rely upon. And when COVID-19 struck, they suffered proportionally greater job loss. Yet, many in these groups have more people depending on them financially, meaning their money has to stretch further. For example, over half of millennial women live with their minor children compared with 32% of millennial men, and nearly 1 in 5 black millennials provide regular financial support to someone outside their household while only 8% of white millennials do so. Many financially vulnerable millennials thus face the necessity of doing more with less; the COVID-19 pandemic makes that stark reality even more overwhelming.

Can Millennials Recover?

Young adult Americans are facing very serious economic upheaval. As a group, they had not yet fully recovered from the Great Recession when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. For some, this meant piling income and job loss on top of small or nonexistent wealth buffers. Some millennials—particularly those who are black, Hispanic or women, or who have less than a bachelor’s degree—were already financially vulnerable going into the pandemic. Many lacked the financial health to withstand this blow. Millennials' financial fragility hurts not only these individuals, their families and others who rely on them but also the economy as a whole.

The good news, though, is that while not as young as they were during the Great Recession, millennials still have time to recover. The current economic crisis also presents opportunities to pause and rethink how to best achieve household financial stability and resilience against future financial blows. Finally, with many millennials entering positions of power, policymakers may be prompted to think creatively about solutions to help financially strengthen not only this generation but also the ones that follow.

Notes and References

1 Findings presented here use data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking, and the Distributional Financial Accounts from the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors, as well as from the IPUMS-Current Population Survey.

2 In 2019, 63% of Americans reported they would pay for a $400 emergency expense with cash or its equivalent. Of the remainder, the majority said they would meet this expense in other ways. Only 12% of Americans reported they would not be able to pay the emergency expense at all.

3 I use the Current Population Survey unemployment numbers that have not been adjusted for seasonality; doing so would increase these numbers. These numbers are also not directly comparable with initial jobless claims, which is a gross, not net, measure of job loss.

Additional Resources

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions