The College Boost: Is the Return on a Degree Fading?

This is the second post in a series on the financial returns of college degrees.

Our May research symposium, “Is College Still Worth It: Looking Back and Looking Ahead,” identified how the returns to a college degree have changed over time and how those returns can be boosted going forward.

For our Center’s research contribution, we focused on how the financial returns to college have changed across generations. We concentrated on income and wealth outcomes for college graduates born in six decades: Our sample was too thin among families born before the 1930s and after the 1980s to provide reliable estimates.

- 1930s

- 1940s

- 1950s

- 1960s

- 1970s

- 1980s

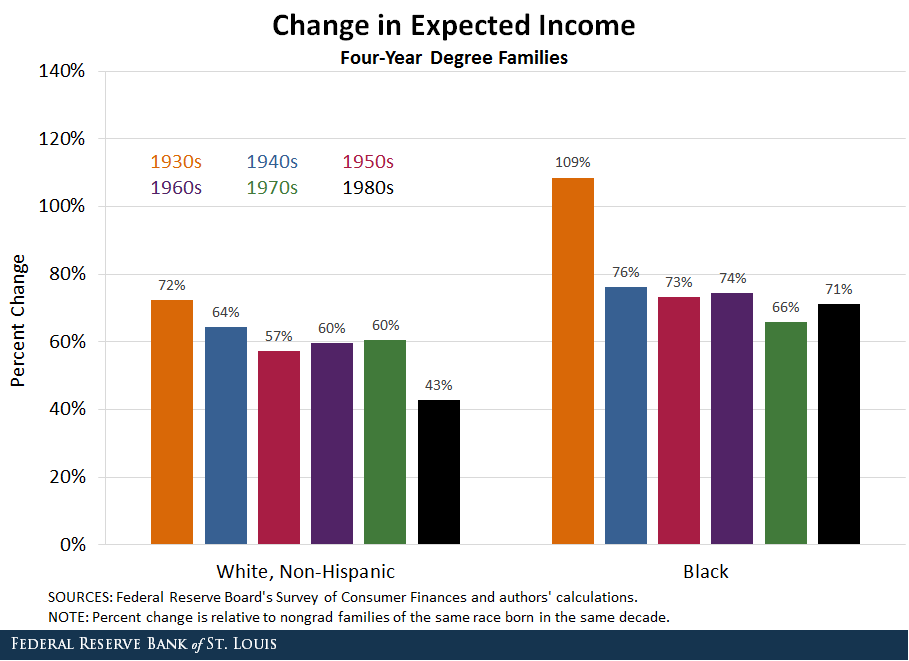

Among racial and ethnic groups, we had a large enough sample to break out our results for non-Hispanic white families and African-American or black families. Similar to the first post in this series, we looked at the boost to income and wealth associated with both four-year (grads) and postgraduate (postgrads) college degrees.

Expected Boost to Income Remains Strong

The figure below shows that expected incomes among grad families of either race have largely held steady across birth cohorts, with the exception of white grads born in the 1980s.

Certainly, the returns were highest among older generations. By our measure, the 1930s generation benefited marvelously from earning a four-year degree. Incomes of grads born in the ‘30s were 72 percent and 109 percent higher than their nongrad peers for white and black families, respectively.

However, given statistical uncertainty or “noise,” we can’t definitively say that the incomes of grads born in the ‘30s were meaningfully higher than grads born in the ‘40s through ‘70s. This tells us that the expected boost to earnings associated with a four-year degree remains largely unchanged over time.

We can say that for white grads born in the ‘80s, their incomes were meaningfully lower than those of previous generations. However, it’s important to note that even the ‘80s grads received a sizable boost to their income. Thus, it appears that grad families of either race, born in any decade, reaped sizable rewards in the labor market.

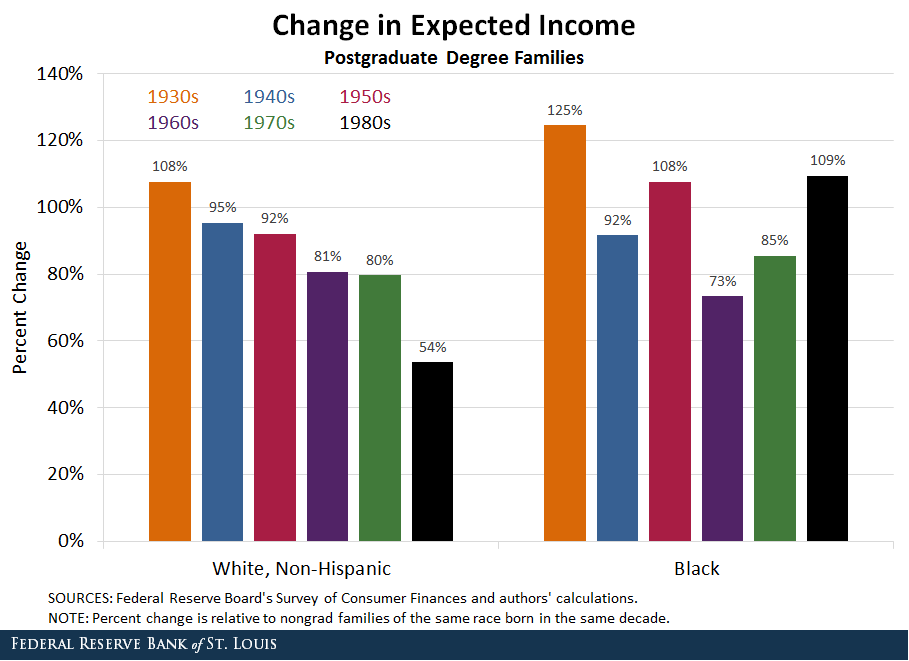

What about postgraduate degrees? The next figure offers a similar look at the income boost among these highly educated families.

Expected earnings associated with a postgraduate degree have declined somewhat over time among white families. Returns peaked at 108 percent higher income for postgrad families born in the '30s and gradually shifted down to 54 percent for the postgrads born in the '80s.

Among black postgrads, the earnings boost is considerably more volatile across generations. After looking at the statistical noise related to these estimates, we can’t say that the boost to black postgrad income has meaningfully changed over time.

Again, the '80s are a peculiar decade: Similar to their four-year degree counterparts, white postgrads born in the '80s have a lowest income boost than those born in the previous five decades.

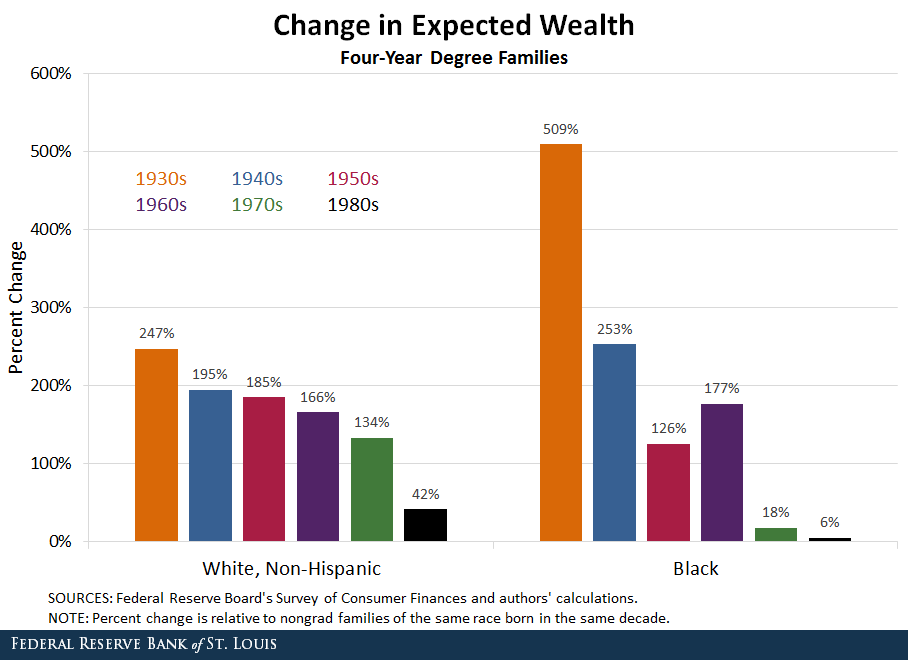

The Wealth Advantage Is Falling

The majority of conversations involving the return to a college degree talk about what graduates earn in the job market following school. This is certainly important, and the evidence suggests that graduates continue to have superior incomes over their lifetime.

What is often obscured is how those graduates accumulate wealth over their lifetime. This is an important difference: Research has shown that assets—financial (such as stocks) and nonfinancial (such as a home)—are profoundly important for both financial security and upward mobility.

If wealth is so important, why is it left out of the conversation? Reliable and nationally representative household balance sheet data are notoriously hard to come by. It is precisely this reason that the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) is such a valuable resource. Using SCF data, we found that the boost to wealth accumulation associated with college has fallen across generations.

The wealth advantages afforded grad families, white and black, are shown in the figure below.

A similar trend emerges: Grad families born in previous generations received a much greater boost to wealth accumulation than their nongrad peers. White and black grads born in the ‘30s accumulated 247 percent and 509 percent more wealth, respectively. This compares with 42 percent and 6 percent more wealth for white and black grads born in the ‘80s.

Black graduates born in the ‘70s also accumulated on average a historically low amount of wealth (18 percent) above their nongrad peers. Disturbingly, given the statistical uncertainty around our estimate for the wealth boost among black grads born in the ‘70s and ‘80s, we can’t say for certain that there even is a wealth advantage to a college degree for the average black family.

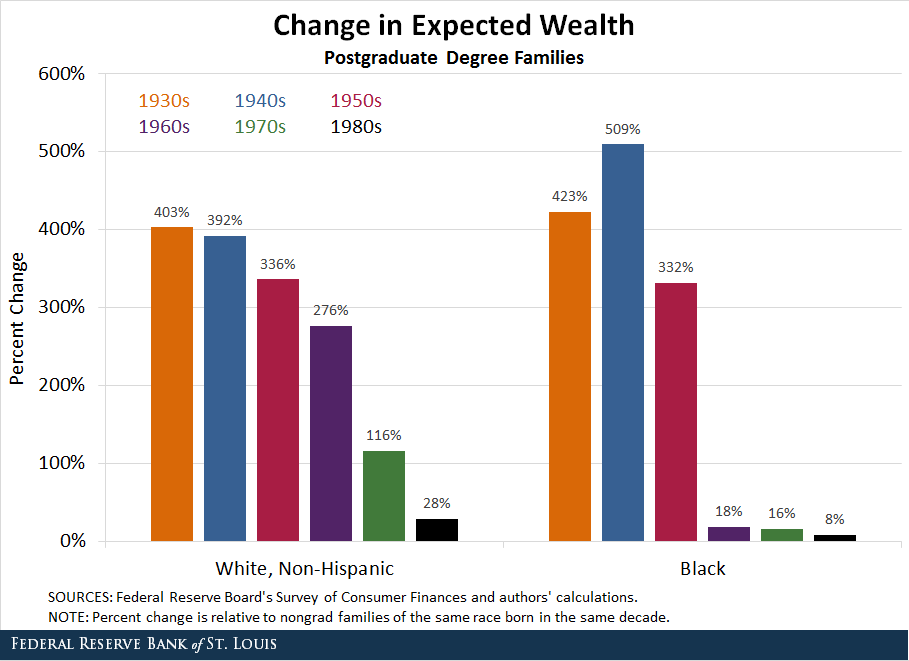

The fortunes of families holding postgraduate degrees are even dimmer by our estimates, as seen in our next figure.

The enormous expected boost to wealth deteriorates rapidly between the ‘50s and ‘80s generations. Among white postgrads, the wealth boost ranged between 403 percent and 276 percent for postgrads born in the ‘30s through ‘60s.

Compare that with those born in the ‘70s and ‘80s, which had 116 percent and 28 percent higher expected wealth than nongrads. The boost estimated for white grads born in the ‘80s is almost negligible after accounting for statistical noise.

The picture is similar for black postgrads, although the decline in the wealth boost starts among postgrads born in the ‘60s. Black postgrads born in the ‘50s accumulated 332 percent more than their nongrad peers. Postgrads born in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s accumulated only 18 percent, 16 percent and 8 percent, respectively, more than their nongrad peers.

All of those estimates were sufficiently noisy that we can’t rule out that they could be zero or even negative. The implication is shocking: Black postgrads born in the 1960s, ‘70 or ‘80s do not have statistically higher wealth than blacks who didn’t graduate from college.

Why have the wealth returns to both a four-year and postgraduate degree fallen so precipitously across birth cohorts while earnings have fared far better? The third and final post in this series will offer some potential explanations.

Notes and References

1 Our sample was too thin among families born before the 1930s and after the 1980s to provide reliable estimates.

Follow The College Boost Series

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions