Household Debt Relief Enters Critical Transition Period

This post is the fifth in a six-part series titled “The State of Economic Equity.” This series examines the challenges facing vulnerable workers this year and possible ways to improve their economic security and resiliency in an economy reshaped by the pandemic.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, an estimated 8.3 million mortgage loans entered forbearance (about 780,720 remain in forbearance); payments and interest for borrowers of federal student loans—the vast majority of student loans—were paused; and many lenders waived fees and deferred payments on a variety of other types of consumer credit, such as credit cards and auto loans.

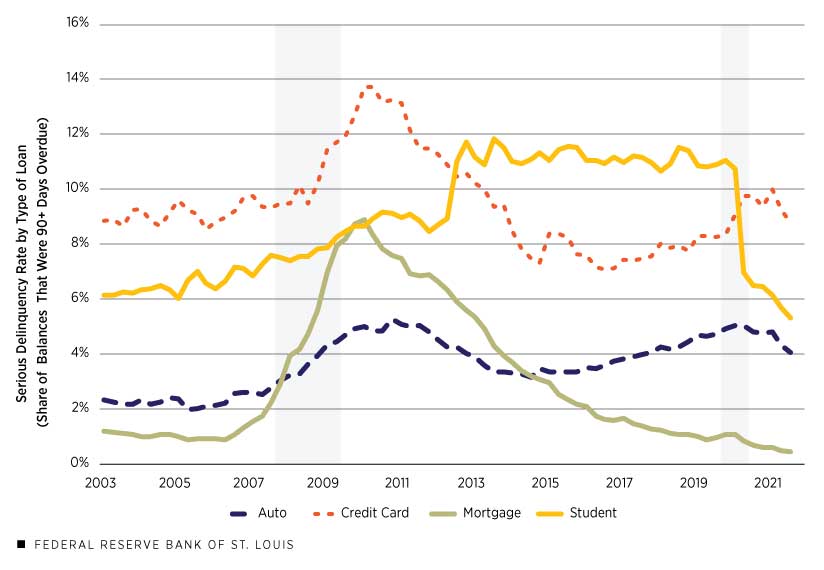

This relief coincided with direct cash support from stimulus checks, expanded unemployment insurance benefits and the temporarily expanded child tax credit. Consequently, serious delinquency rates have been trending down (see the figure below) across all types of debt over roughly the past two years despite the unprecedented disruption.

Rates of Serious Delinquency Have Reached Historic Lows, Yet These Mask Potential Distress

SOURCES: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel and Equifax.

NOTES: The serious delinquency rate is the share of debt that is at least 90 days past due. Shaded areas indicate recessions.

Collectively, a historic crisis has been met with a response that helped buoy many American families in part by lightening the load of their debts.

But a concern is that these policies have already expired or will expire in 2022, ushering in a critical period of debt transition that raises the risk of default and damage to families’ financial stability (e.g., losing a car, damaging credit score). Helping borrowers transition back to sustainable solvency may also require equally thoughtful and proactive responses. Successfully navigating this transition may help maintain economic growth by avoiding disruptions to credit access among low-to-moderate income households.

In addition, it may help avoid deteriorating inequities in consumer debt by preserving the assets (like homes and cars) of low- and moderate-income families, especially Black and Hispanic families. Moving beyond the current crisis presents an opportunity to consider how to reduce consumer debt loads, perhaps in part by mitigating the rising cost of debt-financed assets, such as higher education, homes and cars.

A Time of Transition

While the virus continues to disrupt with new variants, consumer debt relief is transitioning to a resumption of payments and reporting of delinquency. Student loan interest and payments are scheduled to resume after May 1. Serious delinquency rates for student debt could snap back from historic lows to their previous highs in which 10% or more of the debt was past due.

Similarly, the rate of serious delinquency on auto debt has trended down during the pandemic, despite robust growth in subprime loans in the years prior. It remains to be seen if these low rates will continue or if they are a temporary stay of financial hardship due to COVID-19 relief policies.

On the housing front, according to estimates by staff at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 780,720 mortgages remain in forbearance; forbearance will end on 47% of these loans in the first quarter of 2022 and 42% in the following quarter. Based on the timing, the first half of this year may see a spike in loan defaults unless efforts to help borrowers’ transition back to repayment are successful.

Racial Inequities Remain Constant

Like many other outcomes during the pandemic, financial distress has not occurred equally across the population. The Risk Assessment, Data Analysis and Research (RADAR) group at the Philadelphia Fed estimates that as of Jan. 7, 8.6% of Black mortgage borrowers and 6.1% of Hispanic (of any race) borrowers were past due, over double the rate of delinquency of Asian (3.0%) and white (3.7%) borrowers. These racial and ethnic inequities are reminiscent of the severe loss in housing wealth for Black and Hispanic homeowners during the collapse of the housing market and subsequent Great Recession (2007-2009).

Since well before the pandemic, Black families have had to disproportionately rely on financing to pursue a college education. When Black students take out loans, their balances, on average, are significantly higher. For example, among the class of 2016, the average student loan balance was $42,746 one year following graduation for Black students compared with $34,622 for white students, according to data from the National Center for Economic Statistics. Therefore, the resumption of student loan repayments will raise the burden on Black students’ budgets more so than whites.

Less is known about how much of the recent growth in auto lending is concentrated among borrowers of color. Based on the relationship between race and credit scores (PDF), the growth in subprime auto lending is likely indicative of increased debt on the balance sheets of Black and Hispanic borrowers.

Performance of subprime debt usually deteriorates during adverse economic conditions. Though the economy is expected to continue growing in the year ahead, a sudden deterioration in economic conditions could lead to a marked increase in vehicle repossessions. This, in turn, may further damage credit scores and cut off Black and Hispanic borrowers from transportation that they need for work, thus exacerbating labor shortages.

Helping Borrowers Get Back on Track

COVID-19’s spread in child care, school and work disrupted Americans’ income via firm closures, furloughs and the need to provide care. For borrowers who fell behind on payments during the pandemic, loan modification may help them catch up. Policymakers have incorporated lessons learned during the housing crash to mortgage relief during this crisis.

In particular, much of the home-retention options available to borrowers with a mortgage in forbearance are intended to reduce the burden of payments along with requiring less onerous documentation of hardship. Even before the pandemic, student loans had a complex web of repayment plans for borrowers who couldn’t keep up with their payments. In the longer term, simplifying the student loan repayment options may help borrowers and loan servicers alike.

Delivering loan modification support often faces an important policy hurdle: Borrowers must reach out to and work with their servicer to arrange new repayment plans. Whenever the onus is placed on the borrower, information asymmetry (for example, the borrower doesn’t know that the servicer can help them) can be a challenge.

The same coalition of organizations that helped borrowers stay afloat during the worst of the pandemic (government, private sector, consumer advocacy groups and other organizations serving low- to moderate income communities) can work together to reach consumers in need who are unaware of their options.

Repeating mistakes that were made in previous crises may deepen racial inequities in financial outcomes. Successfully navigating this critical time of transition, however, has the potential to keep American families financially whole, support equitable economic growth and affirm a new policy playbook on how to respond to future economic downturns.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions