The State of Economic Equity: Challenges and Opportunities for Advancing Economic Security among U.S. Young Adults

View the full infographic (PDF) for key findings.

Each year, the St. Louis Fed’s Institute for Economic Equity examines the nation’s current economic outlook through an equity lens. This year, our analysis focuses on U.S. young adults (ages 18 to 24). This group has experienced what amounts to two distinct economies relatively early in their lives, one disrupted by a public health emergency and a recession and the other characterized by high inflation and the tightest labor market since World War II.

Recessions raise the risk of weaker financial outcomes, both in the near term and over a lifetime. However, the tight labor market that the U.S. has experienced since early 2022 has provided young adults with economic opportunity. This may offset the COVID-19 pandemic’s adverse economic effects and offer young adults a degree of financial security early in their working lives.

Our focus on young adults is also born of concerns expressed by community stakeholders deeply knowledgeable about workforce development challenges and opportunities in our region. In 2023, the St. Louis Fed’s Community Development team conducted 16 roundtable discussions in communities across the Federal Reserve’s Eighth District.The Eighth District, headquartered in St. Louis, includes all of Arkansas, southern Illinois, southern Indiana, western Kentucky, northern Mississippi, eastern Missouri and western Tennessee. During these conversations, stakeholders repeatedly shared concerns about the structural hurdles that hinder young adults from participating in and benefiting from today’s economy.See this Bridges essay for more about what we learned from these roundtable discussions.

This article describes the economic outlook for young adults from three different perspectives: the labor market, their mental health and their financial outcomes.

A significant number of young adults continue to experience challenges across these areas of focus. For example:

- In 2022, more than one-third of young adults reported earning no income through wages or a salary, up from one-fifth in 1990.

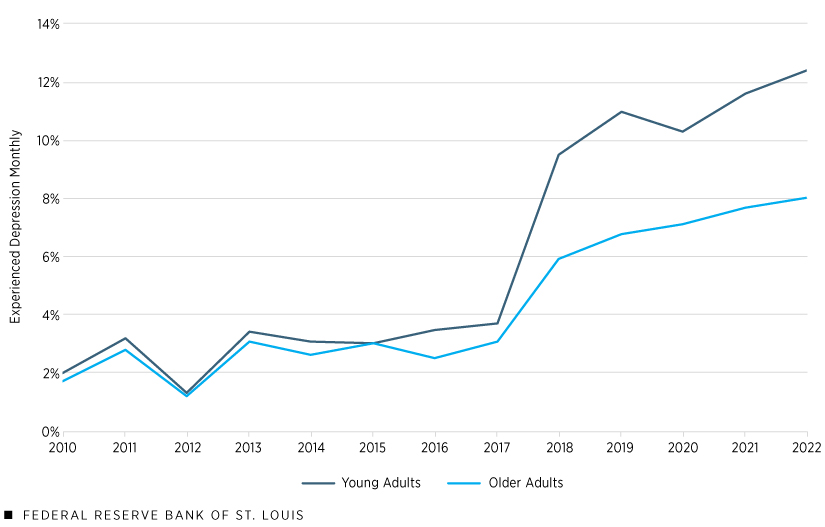

- The share of young adults reporting depression climbed from approximately 4% in 2017 to 12.4% in 2022. The share of older adults reporting depression rose from roughly 3% to 8% over the same period.

- In 2022, the typical (or median) young adult household had a net worth of $11,200, compared with a net worth of $192,100 for all households.

The last section in this article offers an example of how one community is rising to these challenges. It highlights the Hub, a workforce development program in Paducah, Ky. The Hub provides a potential model for how communities can address the structural barriers to participating in the workforce that young adults face.

The Historical and Contemporary Economic Experiences of Young Adults

Are 18- to 24-year-olds in the U.S. today doing better than their counterparts at similar points during previous economic expansions? The answer is complex.

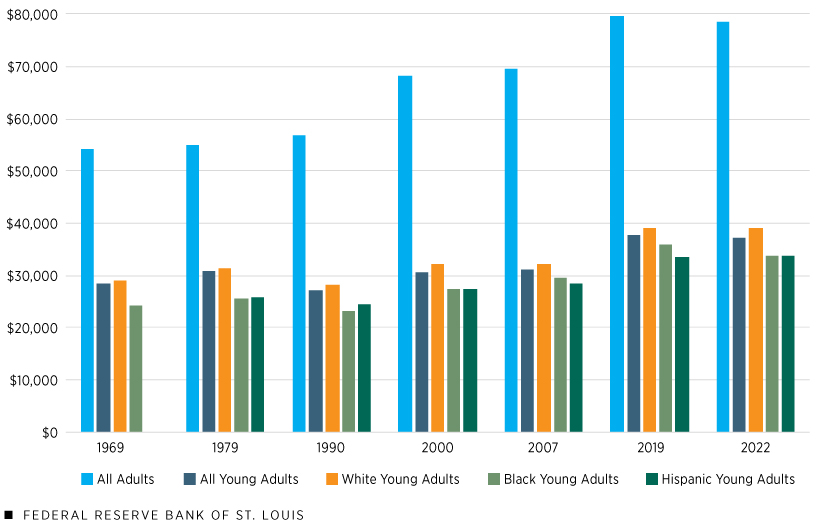

After adjusting for inflation, the average income of all young adults was relatively flat from 1969 to 2007, as illustrated in the figure below. The years shown are peak years of the business cycle, which suggests that they would be those offering the best chance of reducing income disparities. However, young adults’ real incomes only rose above $37,000 in 2019 (their strongest year) and 2022 (almost equally so), $5,000 to $6,000 higher than previously. Since 2019, real wages have again been stagnant not only for young adults from different racial and ethnic backgrounds, but also generally for adults of all ages.

Inflation-Adjusted Young Adult Incomes, Selected Years 1969 to 2022

SOURCES: Authors’ calculations from selected years of Current Population Survey microdata.

NOTES: Young adults are ages 18 to 24. Incomes are measured in 2023 dollars. Data for Hispanic young adults were not available for 1969. Selected years are peak years of the business cycle.

The income estimates in the figure are for young adults who work full time and year-round. In 2019, 35% of young adults reported having no income from wages or a salary—a percentage that had ticked up steadily from 22% in 1990. If these zero-wage young adults are included in the calculation of average annual income, the income growth that occurred after 2007 disappears. This is striking because the labor market in 2022 was the strongest on record, and yet real incomes inclusive of zero-wage young adults remained essentially unchanged as this group made up an increasing proportion of the young adult population.

Who are these young adults with no wages or salary? Many may belong to a group known as disconnected youth: adolescents and young adults that are neither in school nor working. The share of disconnected youth grew after the 2007-09 Great Recession, spiking at around 13% of all young adults before falling in 2019 and then again reaching record highs of nearly 14% in 2020. Disconnected youth are not counted when calculating statistics like the unemployment rate, because they are not considered to be actively looking for a job and are thus not in the labor force.

The large share of young adults reporting no wages presents an opportunity for improving their labor force involvement through interventions like reducing the skills gap, establishing more summer youth employment programs and apprenticeships, and improving access to community college. Targeting structural barriers that impact young adults—such as mental health, discrimination, the criminal justice system, and lack of access to child care and transportation—could improve employment outcomes. Workforce challenges that young adults face include skill-building, job entry and job maintenance. Collectively, support in these areas could help build the foundation for stronger future economic growth.

Young Adults’ Mental Health Needs: Deepening Economic Disparities

Mental health challenges can lead to weaker labor market attachment. Conversely, weak attachment to the labor market can potentially affect mental health. For instance, inability to hold a job may result in stress and anxiety. Whichever direction the causality occurs, mental health challenges among U.S. young adults can act as a barrier to income and wealth creation.

For example, depression has been associated with a lower GPA and a higher risk of dropping out of college, which could lead to lower educational attainment that limits both employment opportunities and earning potential. For those working, mental health episodes can lead to increased absenteeism (PDF), job turnover and lost productivity.

Barriers to mental health treatment can introduce additional financial burdens related to health care costs for therapy, medication and even hospitalization. High health care expenses can strain financial resources, exacerbating the economic impact of mental health challenges, especially for those without adequate insurance coverage. Consequently, without affordable, accessible treatment, income instability further perpetuates wealth disparities.

In 2019, 50 million people in the U.S.—or 1 in 5 Americans—had a mental health condition (PDF). According to the World Health Organization, mental health is a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well, work well and contribute to their community.

Over the past 15 years, the proportion of the population reporting mental health issues has increased, intensifying during the COVID-19 pandemic. The figure below shows that reports of depression have risen among both young adults (again, ages 18 to 24) and older working-age adults (ages 25 to 64) since 2010. The increase disproportionately impacted young adults. While the data were processed differently beginning in 2019,A significant decline in response rate to the National Health Interview Survey required a change in method for nonresponse correction and creation of the final sampling weights. Readers are advised not to compare pre-2019 with post-2019 values. Please refer to IPUMS NHIS for more details. they clearly demonstrate that the depression rate among young adults started to diverge from the depression rate among older adults in 2017, creating a gap of 4 percentage points between these groups by 2022.

Rise in Depression: Young Adults vs. Older Adults, 2010 to 2022

SOURCES: National Health Interview Survey (2010-22) and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: Young adults are ages 18 to 24. Older adults are ages 25 to 64. Data show weighted mean values for the percentage of adult respondents who felt depressed monthly.

Several interconnected factors may have contributed to the rise in young adult mental health issues, such as social media, family structure, and the prices of child care, college tuition and housing. While the need for mental health care has risen, it’s also true that more young adults are speaking to mental health professionals today than they did in the past. Insurance changes within the past decade have allowed young adults to stay on their parents’ insurance until age 26, potentially increasing their access to treatment. Provider access has also grown through the emergence of telepsychiatry, which can reduce wait times, the need for transportation and time off from work for appointments.

Even though insurance coverage and treatment opportunities appear to have expanded, the share of young adults who reported needing mental health care during the previous 12 months but could not afford it remained relatively unchanged between 2000 and 2018. Furthermore, during the pandemic, the substantial surge in the need for mental health care outpaced the advances in access. Additionally, access to mental health care providers is unequally distributed by geography and race. This access could improve as broadband internet expands to rural and other underserved communities.

Addressing young adults’ mental health needs is beneficial for the well-being of individuals, but it also has broader societal implications for economic equity. Building supportive communities that foster inclusivity and provide resources for mental health awareness and education may help bridge care gaps. Accessible and effective mental health services could contribute to breaking the cycle of mental health-related economic disparities among young adults.

Wealth Gaps Emerge Early: Economic Consequences for Young Adults

It is no surprise that young adults tend to be in a weaker financial position than older working-age adults. Their attachment to the labor force is developing, they are acquiring debt (e.g., to pay for education or a mortgage), and they have lower-valued assets. In 2022, the typical (or median) young adult household had a net worth of $11,200, compared with $192,100 for all U.S. adult households.

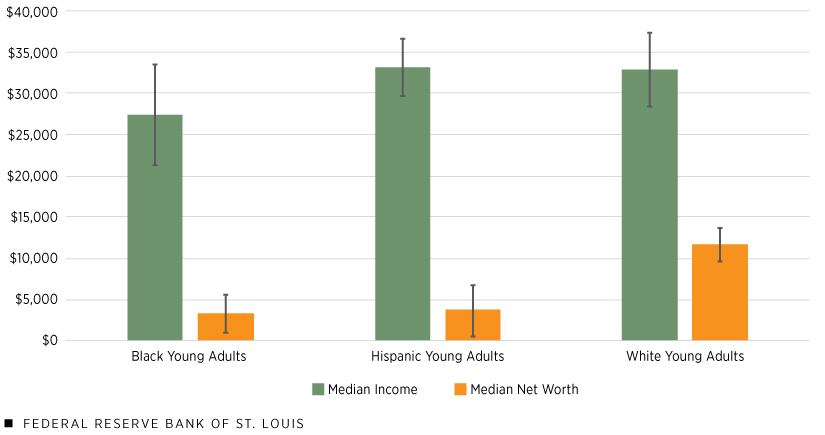

Financial outcomes tend to follow a natural cycle by age; having relatively low levels of wealth is normal for younger adults. That said, disparities exist among young adults of different races and ethnicities. For example, the figure below shows that the typical income among Black, Hispanic and white young adults is largely similar. However, wealth levels are significantly lower for Black young adults and Hispanic young adults than they are for their white peers.Income and wealth data are pooled for the 2016, 2019 and 2022 waves of the Survey of Consumer Finances. This highlights the well-documented racial wealth gap.

Black-White and Hispanic-White Income and Wealth Gaps among Young Adults

SOURCES: Survey of Consumer Finances and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: Young adults are ages 18 to 24. Bands indicate 90% confidence intervals. Data are pooled for the 2016, 2019 and 2022 survey years. Households are grouped using the demographics of the survey respondent.

The implications of lower net worth for all young adults, and especially for Black young adults and Hispanic young adults, are reduced financial security and less economic mobility. A lack of wealth, especially liquid wealth such as money in a checking or savings account, generally means that young adults have fewer resources to access in the event of an emergency or unexpected expense. For example, according to our analysis of the most recent Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED), 33% of Black young adults and 27% of Hispanic young adults would be completely unable to cover a $400 emergency expense (versus 15% of white young adults).

Also, young adults have fewer funds to invest in their futures, whether that involves owning a home, starting a small business, saving for retirement or other financial goals. This is reflected in very low levels of median wealth, as shown in the figure above, as well as subjective assessments of financial well-being. Using SHED, we found that even for young adults, the variation in financial well-being is wide: 76% of white young adults and 73% of Asian young adults reported doing at least OK financially, whereas 53% of Black young adults and 56% of Hispanic young adults said they were doing OK financially.

Wealth disparities among young adults can impact the broader economy: More-equitable wealth outcomes could help drive economic growth and innovation. In past work, we compared two hypothetical families: the Chamberlains and Halloways. They are similar in many ways, but the Chamberlains are wealthy and the Halloways are not. When their children reach young adulthood, the Chamberlains’ daughter, Michelle, and the Halloways’ son, Kevin, both go to college. Both sets of parents assist financially, but Kevin still needs to take out student loans, while Michelle does not. While Kevin is at school, his dad becomes ill but lacks good health insurance. Consequently, Kevin becomes a part-time student so that he can work to help his family financially. Michelle’s family, on the other hand, doesn’t have to worry about health-related financial hardships. She can take an unpaid internship the summer before her senior year, which leads to a well-paying job. Upon his graduation two years later, Kevin is saddled with student debt and is already financially behind. He may delay asset accumulation, such as homeownership, for example, while Michelle is well on her way toward economic security and upward mobility.

An Innovative Approach for Young People to Explore Career Paths

Young adults are at a stage in their lives during which they are building skills, working their first jobs, and taking their first steps toward financial security. These are important experiences as young adults progress into later adulthood and continue contributing to and deriving benefits from the economy.

Experiences at this critical juncture are not the same for everyone. For instance, young adults in the most recent cohort (those now ages 18 to 24) have experienced a global pandemic and its social and economic implications, the effects of which may be studied for years to come. Additionally, mental health challenges seem to be impacting this age group more so than others, a factor that could affect both labor market experiences and financial outcomes. Many young adults, especially disconnected youth, are facing these economic headwinds. However, such headwinds are stiffer for some groups than others.

Paducah Tilghman High School 11th grader Ethan Burdette participates in the SkillsUSA Auto Technology competition at the Hub. Burdette, who placed third in the region, has earned several ASE certifications.

Despite the challenges, it is still “an exciting time to be a young adult,” says Steve Ybarzabal, principal of the Paducah Innovation Hub (or simply “the Hub”). Every time he hears about the skills shortage in the U.S. labor market, he says he thinks about opportunities for young people participating in many of the programs the organization offers.

The Hub was established in 2019 to help students explore careers in the traditional trades (e.g., carpentry), health care and technology. It cost $24.3 million to open, and when walking into the building, one might mistake it for a Silicon Valley tech company. It is on the campus of Paducah Tilghman High School, which makes it easy for students there to access programs that train them in robotics, engineering, computer-aided design, and more.

Paducah Tilghman High School 11th grader Braelynn Hutcherson plans to finish the Hub’s two-year welding pathway in spring 2024. Hutcherson wants to pursue a work-based learning experience her senior year and a career as a welder after graduation.

Within the Hub, Paducah public school students from kindergarten to high school can access its Makerspace programming for free. Students can learn a variety of skills, from laser engraving to programming used in virtual reality. The Area Technology Center, which is part of Kentucky’s career and technical education initiative, is also housed there. Students from nearby counties, some private schools and even home-schools can attend classes that touch a variety of careers, from welding and health sciences to information technology and transportation.

Ybarzabal says the rationale for establishing an approach like the Hub was based on three community objectives:

- There was a need for an economic strategy to address growing demand for skilled workers in the region.

- Students often asked educators, “Why do I need to learn this?” The Hub can offer students a clearer view of future career opportunities.

- Retaining talent can help build a stronger community. Relationships between students and industry partners could encourage graduates with employment prospects to stay in the area or return after further education, a boon for small or rural communities seeking to attract and retain workers.

At the Hub, students develop both soft and hard skills that are readily applicable in the workplace. According to Ybarzabal, their learning is based on five pillars: communication, teamwork, fluid intelligence, innovation and problem-solving. Innovative community spaces like the Hub can help prepare young adults for tomorrow’s workforce and an economically secure future.

Advancing the Economic Security of Young Adults

In relatively quick succession, young adults in the U.S. have experienced the COVID-19 pandemic, an economic downturn and high inflation. Even so, their resilience is evident in the economy’s rapid recovery. Despite the strong labor market recently, structural barriers to labor force participation that existed prior to the pandemic continue to act as barriers to financial stability and economic mobility among young adults.

For example, mental health challenges are an increasingly important factor constraining the opportunities of young adults. While people—regardless of age—are more aware of mental health issues and wellness, care remains inaccessible to many. Class, along with race and ethnicity, remain powerful factors influencing one’s ability to deal with systemic barriers to mental health care, employment opportunities and wealth accumulation.

Investments in young adults could increase their ability to interact with the economy while enhancing worker productivity, innovation and growth beneficial for fostering a healthy economy. Resources like the Hub may offer a model for communities to invest in their young people and their own prosperity.

Notes

- The Eighth District, headquartered in St. Louis, includes all of Arkansas, southern Illinois, southern Indiana, western Kentucky, northern Mississippi, eastern Missouri and western Tennessee.

- See this Bridges essay for more about what we learned from these roundtable discussions.

- A significant decline in response rate to the National Health Interview Survey required a change in method for nonresponse correction and creation of the final sampling weights. Readers are advised not to compare pre-2019 with post-2019 values. Please refer to IPUMS NHIS for more details.

- Income and wealth data are pooled for the 2016, 2019 and 2022 waves of the Survey of Consumer Finances.