College Freshman Enrollment Drops during Pandemic

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- First-time college enrollment fell in 2020 as health and online learning concerns arose during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Two-year schools saw the largest drop in freshman enrollment, while four-year, private, for-profit schools saw the biggest increase.

- The overall drop could be attributed to students delaying their enrollment at least until spring 2021.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continued, first-time fall college enrollment fell 13% in 2020, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. This estimate likely understates the total decline, since it excludes first-time international students, whose attendance was estimated elsewhere to have dropped by more than 40%.See, for example, this IIE snapshot.

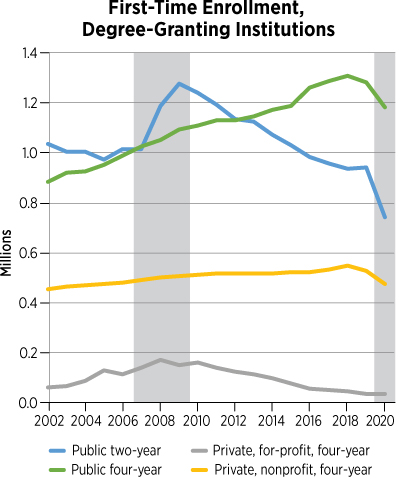

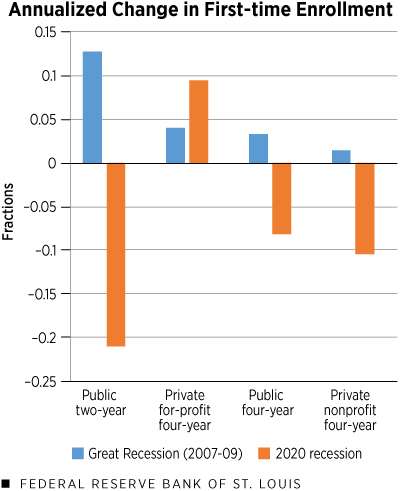

What is behind this sharp enrollment decline? In the figure below, the first panel depicts trends in freshman enrollment by institution type. The second panel compares the 2019-20 enrollment growth rates for each institution type (in orange) to enrollment growth rates during the Great Recession of 2007-09 (in blue). 2020 enrollment declined significantly in all but the four-year, private, for-profit sector.

College Enrollment Changes over Time

SOURCES: Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (NSCRC) and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: For 2002-18 (when IPEDS data were available), we plotted first-time fall enrollment using IPEDS data; the series are extended to 2020 by applying the Research Center’s estimated, sector-specific rates of change in first-time enrollment from its 2020 Term Enrollment Report. IPEDS defines first-time students as students attending an institution with no postsecondary experience after high school graduation. Gray areas in the top panel indicate recessions.

The decline in freshman enrollment in 2020 stands in stark contrast to the enrollment dynamics during previous recessions. Typically, as unemployment rates increase during a recession (especially for younger workers), more people decide to enroll in college. This is because the opportunity cost of postsecondary education—its cost compared with other alternatives—declines as its perceived benefit rises.

Moreover, this change in freshman enrollment happens predominantly in two-year colleges. This is because marginal students—those on the margin of entering or foregoing college—are most sensitive to small changes in the costs or benefits of college.

A majority of these students get weaker grades in high school and college, and leave college before earning a bachelor’s degree.See Hendricks and Leukhina (2017) and Hendricks and Leukhina (2018). They typically enroll in two-year public colleges because of their affordability, proximity to home, open-door admissions policies and two-year degree options.

The figures above clearly show this conventional wisdom at work during the Great Recession. They also show that 2020 was a different story. Even though the summer of 2020 featured high unemployment rates, freshman enrollment declined—and two-year colleges experienced the most dramatic drop (22%).

Why the Overall Drop in Enrollment?

Casual investigators might assume the decline in first-time college enrollment for the fall of 2020 was driven by lower high school graduation rates in the spring. Indeed, the sudden pivot to online learning left many students, teachers and onlookers anxious.

News articles at the time frequently emphasized students’ difficulty with remote learning, which certainly makes this a reasonable concern.For instance, one Wall Street Journal article reported that students returning to school in the fall would do so having made less than half of the typical yearly learning gains in math during the 2019-20 academic year, and that roughly 1 in 5 students nationwide lacked a reliable internet connection for remote learning. However, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center estimates that high school graduation rates remained stable last year,See the 2020 High School Benchmarks report. and data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) show an increase in the fraction of 18-year-olds who graduated from high school by summer 2020.The Wall Street Journal article previously cited gives one possible explanation for this: Many schools were especially hesitant to fail or even grade students last spring, specifically because of these difficulties, which may have made it easier for seniors to coast through graduation.

A decline in the absolute number of college-aged Americans also could have caused a drop in total enrollment, even in the face of increasing high school graduation rates. However, CPS data show no such decline.In fact, the Census Bureau projects no consistent decline in the 18- to 24-year-old population through 2060.

It follows that the drop in freshman enrollment was driven by a drop in enrollment rates from the most recent cohort of high school graduates.Of course, enrollment from other groups—for instance, people who took a gap year between high school and college—could also be a factor, but they historically comprise a small fraction of college entrants.

Why Were High School Graduates Less Likely to Enroll in the Fall?

First, incoming students likely perceived the benefit of enrolling in college to be lower. One important aspect of the freshman experience is the social life on campus; with this prospect shattered by the pandemic, many may have chosen to delay their college entry.

One July survey reported that 40% of incoming freshmen bound for four-year schools were likely to defer their entry at least until spring 2021. These students also expressed health concerns related to in-person instruction and were skeptical about the benefits of remote learning.In particular, nearly 1 in 5 incoming freshmen didn’t trust their college to “take the necessary precautions to keep students safe,” and nearly three in four expressed concern they might contract COVID-19 if they went to in-person instruction in the fall. But only half preferred taking all classes online over taking some or all classes in person. These concerns, especially those about online instruction, undoubtedly extended to two-year public colleges.

Second, the financial strain and future uncertainty caused by the pandemic made college less affordable for many families.See, for example, this survey by OneClass, which found that more than half of college students said they could no longer afford tuition because of COVID-19. Potential enrollees may have expected less help from their parents and faced greater out-of-pocket costs to attend college.

These smaller benefits and larger costs of college may have been powerful enough to cause a decline in freshman enrollment, even in the face of weaker labor market conditions.

Why the Dramatic Decline at Two-Year Colleges?

As mentioned, two-year colleges tend to enroll marginal students—the group most sensitive to small changes in the costs and benefits of college. Two-year colleges also host more students from low-income families, for whom the pandemic-induced financial strain and college affordability were most relevant.See this NPR article on 2020 enrollments, which touches on this concern. Therefore, it is not surprising that, as the cost/benefit analysis made college less attractive for incoming freshmen, two-year colleges lost more of their students.

We also argue that a chunk of two-year (and, possibly, other four-year) enrollment was lost to the four-year, for-profit sector, for the following reasons:

- For-profit schools have established remote learning programs and might be considered superior to two-year schools in delivering online instruction.

- For-profit schools are the least selective among four-year schools and could easily accommodate an influx of marginal students.

- With respect to degree choices, for-profit, four-year schools are more similar to two-year schools than other four-year institutions.

An April survey found that, among the incoming freshmen who still planned to enroll full time in the fall, nearly a third reported being more likely to consider an online degree program. This reveals an increased (though still minority) preference for remote learning.

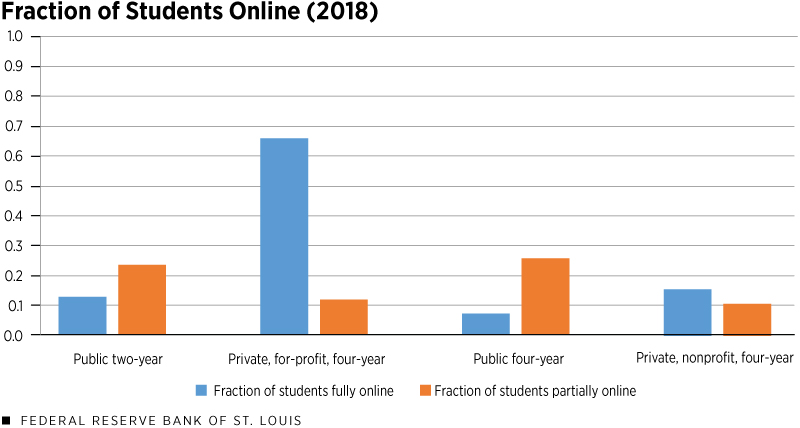

The increase in enrollment at four-year, private, for-profit schools (which was small in absolute terms, but represented a more-than 10% increase from 2019) supports this stated preference. Even before the pandemic, many for-profit schools aggressively marketed their online courses; IPEDS data show that, weighed by their enrollment, more than 20% of for-profit colleges were fully online in 2019,Specifically, as weighed by their fall 2018 enrollment (the latest available fall enrollment data). This compares to 5% of private, nonprofit, four-year colleges and almost no public two-year or four-year colleges. and a much higher fraction of students in that sector were already fully or partially online, compared to other students at other colleges in 2018. (See the figure below.)

SOURCES: Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: Here, we rely on 2018 fall enrollment—the latest-available fall enrollment numbers from IPEDS.

It is likely that—caught between health concerns from in-person classes and a possible distrust toward online courses—some students turned to for-profit schools, many of which had existing (and previously advertised) remote learning infrastructures and may have been seen as more credible providers of online instruction.

It also would have been relatively easy for those who normally attend two-year public colleges to pivot to this sector because its admission standards are relatively weak. IPEDS data show that students’ SAT scores at private, for-profit, four-year schools were lower than at other four-year schools on average, though they were still higher than those at two-year schools.

Finally, for-profit, four-year schools are far more likely to offer associate degrees than other four-year schools.Per 2019-20 IPEDS data. Insofar as community college starters seek these two-year degrees over four-year degrees, this availability of two-year degrees at for-profit “four-year” schools would make them a better-seeming substitute for degrees from two-year public schools, further driving enrollment changes.

Conclusion

The historic decline in 2020 enrollment is driven predominantly by those who normally attend two-year public colleges. This in turn is driven by high school graduates, many of whom planned to delay or forego college entrance in the face of pandemic-related health concerns, or because of lack of interest in remote learning and declining affordability.

Four-year, private, for-profit schools, which have marketed themselves in years past as centers for online programs, have been least affected by these concerns, apparently luring a small segment of students who decided not to delay their enrollment and who may normally have attended elsewhere.

References

Hendricks, Lutz; and Leukhina, Oksana. “The Return to College: Selection and Dropout Risk.” International Economic Review, August 2018. Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 1,077-1,102.

Hendricks, Lutz; and Leukhina, Oksana. “How Risky is College Investment?” Review of Economic Dynamics, October 2017. Vol. 26, pp. 140-163.

Endnotes

- See, for example, this IIE snapshot.

- See Hendricks and Leukhina (2017) and Hendricks and Leukhina (2018).

- For instance, one Wall Street Journal article reported that students returning to school in the fall would do so having made less than half of the typical yearly learning gains in math during the 2019-20 academic year, and that roughly 1 in 5 students nationwide lacked a reliable internet connection for remote learning.

- See the 2020 High School Benchmarks report.

- The Wall Street Journal article previously cited gives one possible explanation for this: Many schools were especially hesitant to fail or even grade students last spring, specifically because of these difficulties, which may have made it easier for seniors to coast through graduation.

- In fact, the Census Bureau projects no consistent decline in the 18- to 24-year-old population through 2060.

- Of course, enrollment from other groups—for instance, people who took a gap year between high school and college—could also be a factor, but they historically comprise a small fraction of college entrants.

- In particular, nearly 1 in 5 incoming freshmen didn’t trust their college to “take the necessary precautions to keep students safe,” and nearly three in four expressed concern they might contract COVID-19 if they went to in-person instruction in the fall. But only half preferred taking all classes online over taking some or all classes in person.

- See, for example, this survey by OneClass, which found that more than half of college students said they could no longer afford tuition because of COVID-19.

- See this NPR article on 2020 enrollments, which touches on this concern.

- Specifically, as weighed by their fall 2018 enrollment (the latest available fall enrollment data). This compares to 5% of private, nonprofit, four-year colleges and almost no public two-year or four-year colleges.

- Per 2019-20 IPEDS data.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us