Why Do Women Outnumber Men in College Enrollment?

When the fall college enrollment numbers came in, we learned that, for every man, there are now almost two women attending college. These numbers indicate the highest recorded gender imbalance favoring women seen in U.S. college enrollment. The media discussion that ensued (for example, see this WSJ article) has, for the most part, sympathized with the young men and focused on identifying possible causes of such a stark gender imbalance. Questions were raised: Are girls receiving preferential treatment in high school and boys increasingly slipping through the cracks? Did the recent change in SAT scoring disproportionately favor female test-takers? Are the college admissions to blame?

In this blog post, we argue against these explanations, showing it is unlikely that the gender gap in college attendance reflects some sort of failure on the part of educators or college admissions officers. A more likely explanation is that the labor markets reward women with relatively higher financial returns to college enrollment.

Women Outnumbering Men in College

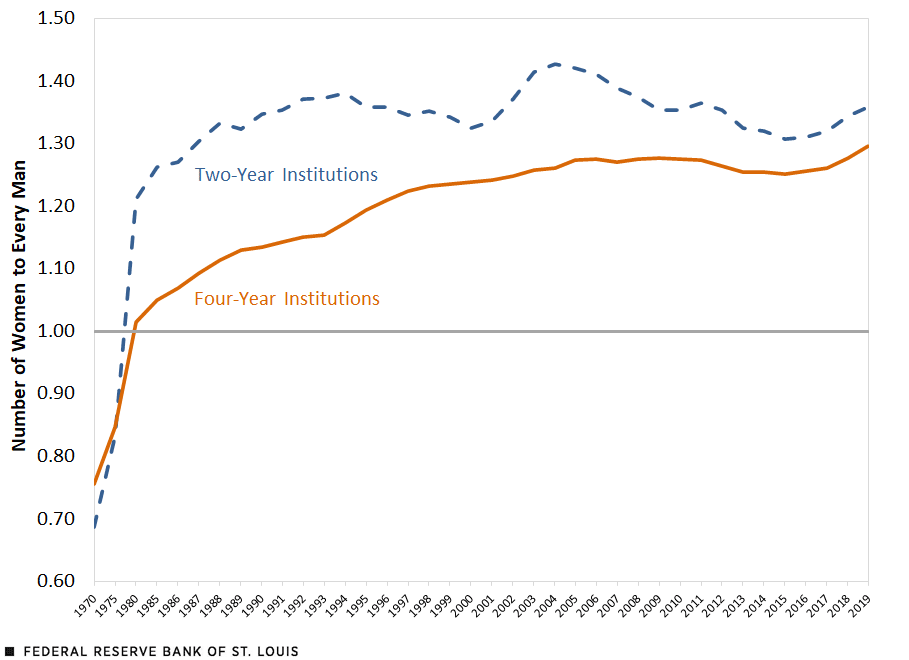

Let’s begin by looking at the next figure, which shows how the relative female-to-male undergraduate enrollment (the gender enrollment gap) at two-year (blue line) and four-year (orange line) institutions evolved over time.

Female-to-Male Ratio in Undergraduate College Enrollment

SOURCES: National Center for Educational Statistics, Higher Education General Information Survey (HEGIS), Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: Our sample consists of degree-granting, Title IV-complying undergraduate institutions from 1970 to 2019; data before 1986 were available only every five years. Undergraduate enrollment encompasses all students enrolled at these institutions regardless of year or attendance status.

In 1970, men outnumbered women in college, accounting for 59% of undergraduate enrollment in two-year institutions and 57% in four-year institutions. This was partly due to the high numbers of men enrolling for the purpose of avoiding conscription during the Vietnam War. In fact, the gender enrollment gap closed sharply as soon as the draft ended in 1973. By 1980, gender was perfectly balanced in four-year colleges, and women outnumbered men in two-year schools, accounting for 55% of enrollment in those institutions.

Since 1980, the female-to-male ratio in two-year college enrollment continued to increase until it hit about 1.4 in 1995, stabilizing at that point. The relative female-to-male ratio in four-year college enrollment, however, increased steadily throughout this time period, reaching 1.3 in the fall of 2019.

What all of this means is that the stark gender imbalance featured in recent media discussions is simply a continuation of an ongoing historical trend and that no recent policy change (e.g., reforms in SAT scoring) can explain the presence of a historical trend.

Academic Performance

One potential reason that could explain this trend is a similar one in the relative academic performance of girls versus boys at the high school level. If girls are increasingly outperforming boys in high school—whatever the reasons may be—it would make sense that they would increasingly outnumber boys in college (although this would not imply causal influence). If this were the case, we would delve into those underlying reasons.

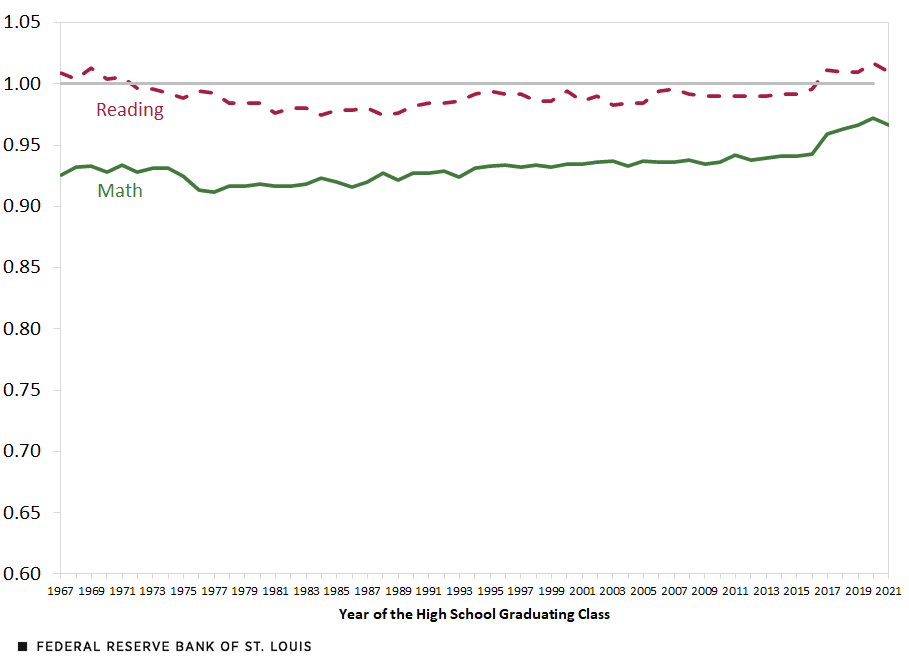

However, it does not appear that there is a systematic trend in the relative performance of boys and girls at the high school level. The next figure shows the relative female-to-male SAT score in reading and math.

SAT Performance: Women’s Scores Relative to Men’s

SOURCE: College Board.

NOTE: The values are averages calculated based on seniors who had taken the SAT at least once. For the class of 2016, the average represents scores through January 2016, capturing the old test version only.

Up until the 2016 changes to the SAT, the relative performance fluctuated around 0.99 for the reading section and around 0.93 for the math section, which indicates that boys scored slightly higher on these tests. There is a slight upward trend for the relative math score, but the change is very small—from 0.93 for the class of 1970 to 0.94 for the class of 2016. It seems unlikely that changes in the relative preparedness for college explain why many more women enroll in college today. If anything, girls are still lagging behind boys in SAT scores.

However, in March 2016, the College Board remodeled the SAT, introducing changes to the structure and timing of different sections, the nature of questions, and scoring rules. It is seen clearly from the second figure that girls’ relative performance on the SAT shot up in the 2017 class, although they continued to slightly lag behind boys in their total score. One potential reason why girls have benefited more from this change is that the College Board tried to make an effort to better align the SAT with high school curriculum, thereby rewarding successful study habits developed in school.

This 2017 uptick in female relative performance on the SAT (the second figure) did coincide with the uptick in their relative enrollment (the first figure), so some causal influence is possible in this case. It would work by helping women be more competitive in the college admissions process. And greater access to higher-quality schools would, of course, increase enrollment.

Relatively Higher Returns to College Education

Nevertheless, the upward trend in relative female enrollment was there already before the 2017 SAT reform, and it is important to understand the forces behind it. We argue that women face greater financial returns to college entry—this is the most likely explanation for why they outnumber men in college today.

To show that women enjoy greater financial returns to college, we examine the variation in real hourly wages among 30- to 40-year-old full-time workers in 2015 census data. The results from the regression estimates are reported in the table below.The estimates are all highly statistically significant; we omit standard errors for simplicity.

| Male Hourly Wage | Difference in the Female Hourly Wage Relative to the Male Wage | |

|---|---|---|

| Those with Only a High School Diploma | $11.93 | -24.4% |

| Difference in Wage for Those with an Associate Degree, Relative to Those with a HS Diploma | 22.3% | 5.3% |

| Difference in Wage for Those with a Bachelor’s Degree, Relative to Those with a HS Diploma | 62.2% | 5.3% |

SOURCES: 2015 ACS data and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: We regressed logarithmic real hourly wage (in 2015 dollars) on indicator variables for sex, associate degree and bachelor’s degree, as well as the interaction terms between each degree type and sex. Using census data for 2015, we consider 30- to 40-year-old full-time workers with at least a high school degree. A full-time worker is defined as anyone who has worked more than 30 hours a week and 35 weeks per year.

The first column reports the statistical results on education group indicators—the high school degree representing the baseline group. It shows that, on average, male workers with a high school degree made about $12 per hour (2.478 in logs) in 2015. Male workers with an associate degree made 22% more, and those with at least a bachelor’s degree earned 62% more.

The second column shows how these estimates differ for female workers. Women with only a high school diploma made about 24% less per hour compared with men in that same education group. Relative to men, women saw an additional 5.3% return to getting an associate or a bachelor’s degree; that is, women with an associate degree made 28% more relative to women with only a high school degree, whereas women with a bachelor’s degree made 68% more.Granted, these numbers should not be literally interpreted as “returns” to getting a degree because workers in different education groups differ on their innate characteristics and those differences partly account for differential wages.

What these numbers reveal is that, indeed, getting more education is an important way to close the gender pay gap. College entry—whether it is to get an AS or a BS—helps women gain access to careers where they have a comparative advantage (e.g., office work). Men on the other hand have better access to lucrative careers that don’t require a college degree (e.g., construction work). This appears to be the most reasonable explanation for why women outnumber men in college.

Why wasn’t this the case in the late 1960s? Why did the female relative enrollment increase gradually over time? This is because fewer married women used to work in the market, so the investment aspect of college was not as relevant in the 1960s. As women increased their labor force participation over time, financial returns to college investment became more important, and more women chose to enter college so as to gain access to more lucrative careers.

More generally speaking, there is no reason to expect a perfect gender balance in college. Women and men face different incentives and should be expected to make different choices.

Notes and References

- The estimates are all highly statistically significant; we omit standard errors for simplicity.

- Granted, these numbers should not be literally interpreted as “returns” to getting a degree because workers in different education groups differ on their innate characteristics and those differences partly account for differential wages.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions