Revamping Medicaid: One State's Attempt at Reform

Throughout most of the mid- and late-1980s, Tennessee's share of its total Medicaid bill grew about 20 percent each year. Between fiscal 1989 and 1990, it climbed almost 44 percent. By the early 1990s, the state was spending about 9 percent of its budget, a share that was expected to rise, on Medicaid.

To stem these rising expenditures, and to extend coverage to a limited number of those who either are uninsurable because of chronic or existing illness, or are uninsured, Tennessee requested a waiver from the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA)—the federal agency responsible for Medicare and Medicaid—to implement a demonstration project called TennCare. HCFA approved TennCare in November 1993; the state implemented it in January 1994. With the waiver, Tennessee replaced its old Medicaid program with TennCare, a program that "required no new taxes and extended health coverage not only to the nearly one million Tennesseans in the Medicaid population, but also to an anticipated 400,000 uninsured or uninsurable persons using a system of managed care."

Program Underpinnings

On the surface, TennCare is exactly what many have called for in health-care reform: privatization of health care in the public sector of the market. The program enlists managed care organizations (MCOs), which, in theory, control costs because they compete for enrollees within a geographic area and use the strength of their enrollment numbers to negotiate low fees for contracted services.1 To allow flexibility, participants can choose among the MCOs in their region during an open enrollment period each year, allowing them to vote with their feet on the adequacy of services received. In some western parts of the state outside the Memphis area, however, there are only two MCOs to choose from.

The state pays a capitation fee—a fixed annual premium—to the MCO, which this year is about $1,500 per enrollee. In exchange, the MCO must provide all necessary medical services to each enrollee. To meet this obligation, the MCO contracts with doctors and hospitals to provide these services at a predetermined fee.

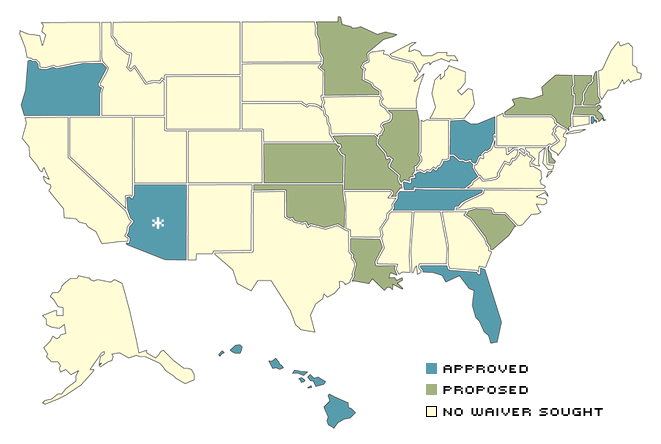

TennCare requires all former Medicaid recipients to join an MCO. "Demonstration-eligible" residents—the uninsurable and uninsured—can also enroll in the program and receive free or subsidized benefits, depending on income level. Total enrollment for demonstration-eligibles, however, is capped by regulation and available state funds. Former Medicaid recipients are entitled to the same benefits they received under Medicaid; demonstration-eligibles are entitled to a more limited package of benefits. After selecting an MCO, each enrollee chooses a primary-care physician who acts as gatekeeper. All referrals for non-emergency services and specialists must be approved by this physician. This set up is supposed to contain costs, as well as allow the patient an opportunity to establish a relationship with one primary-care physician who presumably will be better able to monitor his health care. Most other states with Medicaid waiver proposals pending at HCFA seek to establish similar systems (see chart).

Medicaid Demonstration Projects Currently Operating or Under Consideration

Several states are operating or waiting to operate Medicaid demonstration projects that allow them to engage in locally developed health-care programs. These programs often employ unique proposals to control costs and extend benefits to those not normally covered under Medicaid.

* Arizon has been operating since 1982 as a waiver, after numerous extensions of its original three-year demonstration project.

SOURCE: Rosenbaum and Darnell (1994).

Is It Working?...

Studies on the effectiveness of TennCare's ability to deliver medical care are just now being commissioned; it is still too early to have definitive answers because the system has only been in place for one year. Anecdotes, however, reveal some problems exist in the program.

Some accounts suggest that rationing of care may be occurring, as MCOs refuse to authorize or pay for certain treatments and drugs. Some hospital administrators complain that each MCO has different rules, and that these rules are sometimes changed without warning. A preliminary survey of Tennessee residents conducted in August 1994 indicated that about half of TennCare recipients formerly on Medicaid believe the quality of their health care is worse than that received under Medicaid. The other half thought the care received under TennCare is the same or better than that under Medicaid. In addition, the survey reported that TennCare recipients are more likely than other groups to wait more than three weeks for a doctor's appointment, although the percentage reporting long waiting periods is relatively small for all groups, including TennCare recipients.

According to the Tennessee Health Care Campaign, a consumer coalition monitoring TennCare, one of the most frequent complaints received by its consumer advocacy hotline is the lack of specialists in the MCOs. In three of the state's 12 MCOs, this was the most widely reported difficulty. Nevertheless, during the first six months of 1994, the Campaign handled, as it expected, mostly transition problems as people moved from Medicaid to TennCare. The biggest complaints about TennCare from hospitals and doctors are the MCOs' lower-than-Medicaid payment levels and the amount of time it takes to receive payment. The Tennessee Hospital Association reports that some hospitals have received only 44 cents from TennCare for each dollar of services to patients. Other providers have reportedly been paid between 15 cents and 30 cents on the dollar. Moreover, one of Memphis' largest hospitals providing care to TennCare patients has yet to receive about $50 million from MCOs.2 Furthermore, this facility will lose an additional $42 million previously received under Medicaid because it served a large number of poor patients. This shortfall may force the hospital to forfeit its contract with the University of Tennessee at Memphis for medical residents.

...Controlling Costs?

Tennessee's rising Medicaid costs were actually more severe than many other states' because it had been receiving excess federal monies by exploiting a loophole in the Medicaid program.3 Tennessee was thus able to increase its Medicaid rolls and its federal share of Medicaid funds, while reducing the cost to the state. Other states soon followed until Washington caught on and stopped the practice. Tennessee was then left trying to pay for a larger Medicaid program with fewer federal dollars.

As an example, the state's total Medicaid bill for the first half of fiscal 1994 (July through December 1993) was more than $1.2 billion. Had TennCare not been instituted, Medicaid in Tennessee was projected to cost the state and federal governments more than $6 billion by fiscal 1998. To meet its share of this burden, the state had predicted tax increases of about $200 million per year.

Would these explosive costs have continued to rise? Probably, but no one really knows. Can TennCare help reign in these costs? It is still too early to tell. On paper, the program promises to save both the state and federal governments a considerable amount of money—reportedly $1.5 billion for the federal government alone—over the five-year demonstration period. Comparing Medicaid and TennCare costs is difficult, though, because one can only guess what expenditures would have been had TennCare not been implemented. The state, however, does expect TennCare expenditures to increase at a slower rate than state revenues. By fiscal 1998, the program's total cost is projected to be less than $4 billion.

Can It Possibly Succeed?

The program's architects set lofty goals, which many do not believe can be met. HCFA is keeping a close eye on TennCare's progress because health-care reformers have frequently claimed that by changing the system and capping costs—whether through explicit, legislated caps, or the supposition that privatization will do it automatically—service can be extended to larger numbers of needy residents without increasing taxes. In our District alone, both Illinois and Missouri have similar Medicaid waivers pending, making Tennessee's progress and pitfalls of particular interest. These state-level experiments, aimed at improving the delivery of care under social programs while trying to contain costs, are commendable. The experiments should not be undertaken, however, unless taxpayers and recipients can be assured that their dollars and their care will not be jeopardized foolishly.

Endnotes

- An MCO is a private organization that receives a set fee for each person it enrolls, similar to a traditional health maintenance organization (HMO). [back to text]

- See "Sinking Ship?" (1995). [back to text]

- See United States General Accounting Office (1994) and "Sinking Ship?" (1995). [back to text]

References

Fox, William F., and William Lyons. A Survey to Determine Insurance Status of Tennessee Residents, prepared for the Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration (August 25, 1994).

"Reform Lessons—TennCare: Problems May Show Way To Go," The Commercial Appeal, editorial January 23, 1995).

Rosenbaum, Sara and Julie Darnell. Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration Waivers: Approved and Proposed Activities as of November 1994, prepared at the Center for Health Policy Research, The George Washington University, for The Kaiser Commission on the Future of Medicaid (November 1994).

"Sinking Ship? TennCare's Problems Threaten Med, Others," The Commercial Appeal, editorial (February 10, 1995).

State of Tennessee. Department of Finance and Administration. Tennessee's Health Care Problem—Medicaid (March 1993).

_________. TennCare Fact Sheet (December 1994).

Tennessee Health Care Campaign. TennCare Consumer Advocacy Program—Third Quarter 1994 Report (January 1, 1995).

United States General Accounting Office. Medicaid: States Use Illusory Approaches to Shift Program Costs to Federal Government, GAO/HEHS-94-133 (August 1994).

Related Topics

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us