The Recession's Effect on Job Churn

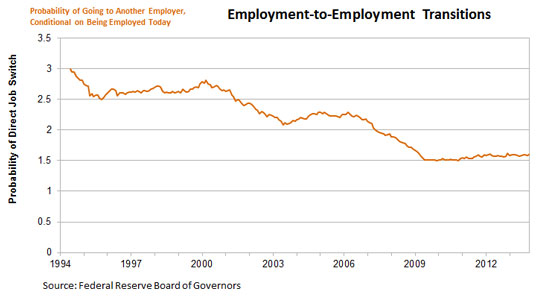

Jobs in the U.S. labor market get turned over at a surprising frequency, with flows into/out of unemployment being almost four times faster than in Germany, despite similar unemployment rates.1 But when U.S. workers leave jobs, they are twice as likely to go directly into another one as become unemployed.2 These job-to-job transitions make up the bulk of the job destruction and creation in the U.S. labor market.

However, it appears that employed workers have slowed their transitions between employers. (Among others, Mike Konczal at The Next New Deal discussed this in a recent blog post.3) While this does not necessarily affect the unemployment rate (as these job-to-job changers are never unemployed), it may be a sign of two things:

- Finding a job is still very difficult.

- The job market may be experiencing coagulation, less churn and less “dynamism.”

If the second point is true, this could spell worrying news for allocative efficiency if we believe that the flow of workers from job to job plays a significant role in efficiently allocating workers.

Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors

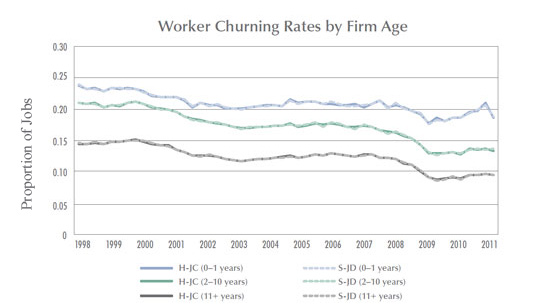

Additional data show not only the flow of workers but also what types of firms they flow to and from.4 Young firms (those less than a year old) have much higher rates of hiring and separations (more churn) than more established firms. However, most workers do not work at such young firms, and the fall has been steady, and not particularly cyclical, from about 5 percent to 3 percent from 1998 to 2011. In the same period, young firms' fraction of new hires fell from about 38 percent in 1998 to its low at 32 percent in 2009, though it recovered slightly. In other words, churn could diminish because all firms are doing less hiring and firing or because young firms, which hire and fire a great deal, are accounting for a smaller fraction of employment. Part of the decline in churn is the changing age profile of firms. The churn rate has fallen since 1998, it fell most sharply in 2009, and, aside from young firms, there has been no recovery.

Note: worker churning is measured in two ways: Hires-Job Creation (H-JC) and Separations-Job Destruction (S-JD). These two measurement should yield identical worker churning, with some variation created by noise used to protect the confidentiality of the data and by seasonal adjustment factors.

Source: Haltiwanger, John; Hyatt, Henry; McEntarfer, Erika; and Sousa, Liliana. "Job Creation, Worker Churning and Wages at Young Businesses." Kauffman Foundation, November 2012.

What does all of this mean? Most simply, some labor market indicators show that we are still not back to prerecession levels. But it also seems that there has been a long-term process behind these sluggish statistics, and the recession only exacerbated it. How does this affect such variables as worker productivity and wages? That demands more work on the theory of worker churn that has yet to be done.

Notes and References

1 Elsby, Michael; Hobijn, Bart; and Sahin, Aysegul. “Unemployment Dynamics in the OECD.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, May 2013, Vol. 95, No. 2, pp. 530-548.

2 Fallick, Bruce and Fleischman, Charles. “Employer-to-Employer Flows in the U.S. Labor Market: The Complete Picture of Gross Worker Flows.” Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2004-34.

3 Konczal, Mike. “Not Just the Long-Term Unemployed: Those Unemployed Zero Weeks Are Struggling to Find Jobs.” Next New Deal, April 17, 2014.

4 Haltiwanger, John; Hyatt, Henry; McEntarfer; and Sousa, Liliana. “Job Creation, Worker Churning, and Wages at Young Businesses.” Kauffman Foundation, November 2012.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: How Important Have Employment Revisions Been the Past Two Years?

- On the Economy: The Rise and Fall of Labor Force Participation in the U.S.

- Regional Economist: Youth Unemployment Notably High in Southern Europe

Related Topics

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions