Disparities by Race, Ethnicity and Education Underlie Millennials’ Comeback in Wealth

In the first post of this series, we found that older millennials (those born in the 1980s) had made significant gains in family wealth. They were only 11% below wealth expectations as of 2019, versus 40% below expectations in 2016. By “wealth expectations,” we mean a predicted level based on the wealth held by families in that generation and earlier generations at similar ages.

In this post, we focus on demographic characteristics within this group to better understand which segments of older millennials are more likely to be behind in expected wealth.The family’s birth year, education, and race and ethnicity all pertain to the survey respondent.

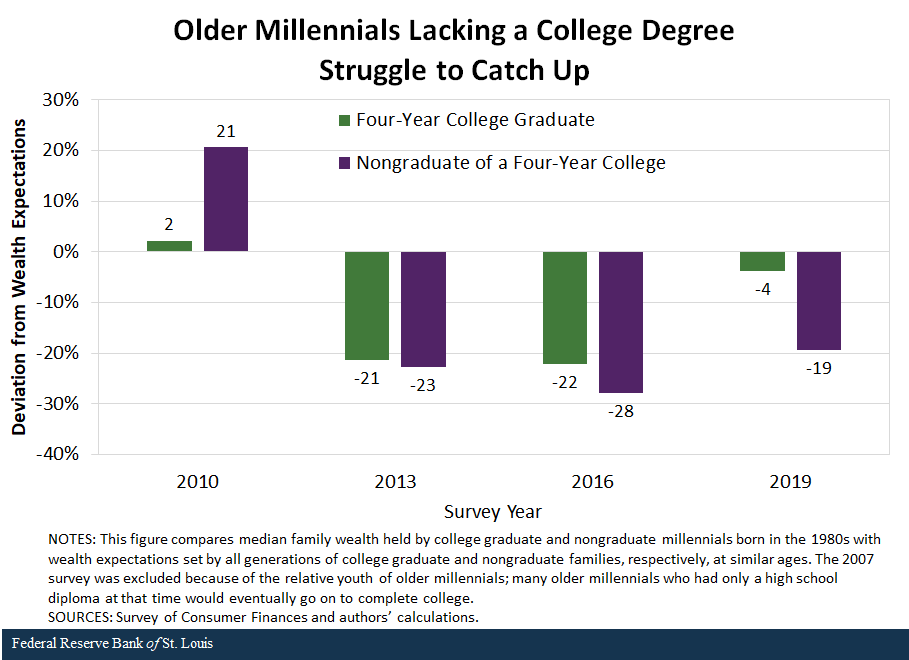

Previous work has shown that families whose head had less than a four-year college degree were a primary reason why older millennials as a whole were falling short of wealth expectations. Using new data and a new methodology,In past work, we have used the birth year of the head (i.e., reference person) of the household. Here, we changed our methodology and used the birth year of the survey respondent, who is generally considered to be the most financially knowledgeable person in a household. In many (though not all) cases, the household’s reference person and respondent are the same. Previous results are roughly comparable with the results presented here. we corroborated these earlier results and also found that older millennials without a college degree remained further below both income and wealth expectations than those with a degree in 2019. [In the case of education, we are comparing the wealth of those having certain education (a college degree or no college degree) in a particular birth decade with a predicted level based on the wealth of all surveyed families of comparable education at similar ages.]

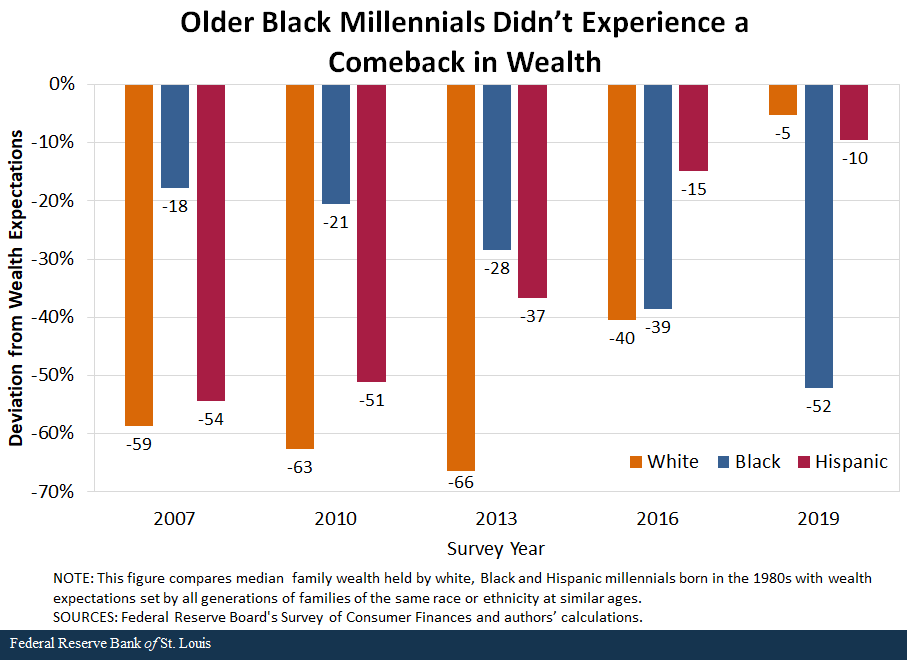

When examining race and ethnicity rather than education, we also found that older white (non-Hispanic) millennials made up significant ground from 2016 to 2019, while older Hispanic (any race) millennials had a more modest recovery. Alarmingly, not only were older Black millennials significantly below wealth expectations, they showed a marked and consistent trend of falling further behind between 2007 and 2019. (In the case of race and ethnicity, we are comparing the wealth of white, Black and Hispanic families in a specific birth decade with a predicted level based on the wealth of all surveyed families of the same race or ethnicity at similar ages.This analysis compares like families with like (e.g. Black families of a certain birth decade with all Black families). Racial, ethnic and educational wealth gaps are thus not captured. For an overview of demographic wealth inequality, and how it has changed over time, see our earlier blog post.

Older White Millennials Reduce Shortfall, while Older Black Millennials Fall Further Behind

Older millennials are more racially and ethnically diverse than previous generations. Only 57% of older millennial families had respondents who identified as non-Hispanic white, compared with 81% of families whose respondents were born in the 1940s.

Regardless of whether they were white, Black or Hispanic, older millennial families as of 2019 were below wealth expectations set by the same racial and ethnic groups at similar ages. However, the magnitude of that shortfall varied greatly. White families were closest to wealth expectations, at 5% below. Hispanic families were 10% below, while Black families were a staggering 52% below wealth expectations. (See the figure below.)

Looking over a longer period of time, older millennial families experienced very different trends, depending on race and ethnicity. While Hispanic families saw steady improvement between 2007 and 2019, and white families rapidly improved between 2013 and 2019, Black families saw the opposite trend. Disturbingly, these Black families steadily fell further and further below wealth expectations between 2007 and 2019. One possible reason is the increasing burden of student loan debt on this group.

Despite notable progress in educational attainment and increasing representation, large racial and ethnic wealth gaps remain within the millennial generation. In the case of older millennials, white families had roughly $88,000 in median wealth, Black families had only $5,000, and Hispanic families had $22,000 in 2019. Such low levels of wealth for Hispanic and especially Black families can hamper both short-term stability (e.g., meeting financial obligations) and long-term mobility (e.g., purchasing a home, saving for retirement).

Yet the income of these three groups in 2019 was roughly on par with expectations, suggesting that their earnings were not holding back wealth accumulation. However, given the large wealth deficit and negative trend, the disparities among older Black millennials may persist as these families age, inhibiting their full participation in the economy.

An Educational Divide

Older millennials are not only more racially and ethnically diverse than older generations but also more highly educated. In 2019, an impressive 44% of older millennial families had at least a bachelor’s degree, a larger share than any previous generation. Rising college enrollment and attainment reflect a widely held belief that a college degree is necessary for economic success. Indeed, we have found that college is financially worth it, particularly in terms of earnings, though the payoff is less clear for younger generations in terms of wealth.

The new data tell a similar story, as shown in the figure below. In 2019, older college-graduate millennials born in the 1980s were 4% below wealth expectations and right on track with income expectations compared with expectations set by college graduates from all generations at similar ages.See our Demographics of Wealth essay for more detail about how we estimate wealth expectations. Older nongraduate millennials were 19% below wealth expectations and 5% below income expectations.

While both older millennials who were college grads and those who were nongrads saw their income and wealth grow relative to expectations between 2016 and 2019, these college grads narrowed their wealth shortfall more rapidly than nongraduates did, by 18 percentage points versus 9 percentage points, respectively. In 2019, the typical older millennial with a degree had $108,000 in median wealth—a shortfall of about $4,000 from expected wealth. Meanwhile, older millennials who did not have a degree had only about $22,000 in median wealth, or a deficit of roughly $5,000. While parents hope their children will be better off financially than they were, the data suggest this is not yet a reality for millennials.

Will Older Millennials Reach Expectations?

Older millennials as a group staged a remarkable comeback in terms of wealth accumulation between 2016 and 2019. However, this analysis highlights inequities within that recovery. While the typical white or degreed millennial born in the 1980s accumulated wealth at a notable pace and largely recovered from a relatively slow start, other groups within the generation had different experiences. While still falling short, older millennials who lacked college degrees and those who were Hispanic still gained relative ground in terms of expectations. However, older Black millennials steadily fell further behind and had very low wealth levels, which left them more vulnerable to unpredictable economic setbacks.

With regard to unexpected setbacks, the latest data here end in 2019, on the eve of the COVID 19 recession. While we do not yet know how the recession has affected the typical family’s wealth,The Real State of Family Wealth report, which is updated quarterly, monitors how generational wealth is affected on average. Given wealth inequality, however, averages tend to reflect families who are better off than the typical American household. (See the appendix of an earlier blog post for more information.) Because the next wave of the Survey of Consumer Finances will be in 2022, it may be some time before we are able to fully understand the impact of the COVID 19 recession on families’ wealth. we have seen disproportionate job loss among Black, Hispanic and nongrad millennials. Given that millennials were already below wealth expectations in 2019, the pandemic may serve as an inequitable headwind across millennial families: weaker for those that had a solid economic foothold and stronger for those that had been making slower gains or even slipping further behind.

Notes and References

- The family’s birth year, education, and race and ethnicity all pertain to the survey respondent.

- In past work, we have used the birth year of the head (i.e., reference person) of the household. Here, we changed our methodology and used the birth year of the survey respondent, who is generally considered to be the most financially knowledgeable person in a household. In many (though not all) cases, the household’s reference person and respondent are the same. Previous results are roughly comparable with the results presented here.

- This analysis compares like families with like (e.g. Black families of a certain birth decade with all Black families). Racial, ethnic and educational wealth gaps are thus not captured. For an overview of demographic wealth inequality, and how it has changed over time, see our earlier blog post.

- See our Demographics of Wealth essay for more detail about how we estimate wealth expectations.

- The Real State of Family Wealth report, which is updated quarterly, monitors how generational wealth is affected on average. Given wealth inequality, however, averages tend to reflect families who are better off than the typical American household. (See the appendix of an earlier blog post for more information.) Because the next wave of the Survey of Consumer Finances will be in 2022, it may be some time before we are able to fully understand the impact of the COVID 19 recession on families’ wealth.

Additional Resources

- In the Balance: Gender Wealth Gap: Families Headed by Women Have Lower Wealth

- On the Economy: Which Families Are Most Vulnerable to an Income Shock? A Look at Race and Ethnicity

- On the Economy: The Real State of Family Wealth: Will COVID-19 Worsen Racial, Educational and Generational Gaps in the U.S.?

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions